- Derivation of Predicted no Effect Concentration of Perfluorooctanesulfonic Acid (PFOS) in Water and Soil Based on Species Sensitivity Distribution Considering Mode of Action

Sang-Gyu Yoon1ㆍWoo Hyun Kim2ㆍYu-Jin Jung1ㆍDahee Hong3ㆍJiyoung Kim1ㆍSung-Hwan Jang1,2,3ㆍTae-Woong Kim1,2,3ㆍIhn-Sil Kwak4ㆍJinsung An1,2,3*

1Department of Smart City Engineering, Hanyang University, Ansan 15588, South Korea

2Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Hanyang University, Ansan 15588, South Korea

3Department of Civil and Environmental System Engineering, Hanyang University, Ansan 15588, South Korea

4Department of Ocean Integrated Science, Chonnam National University, Yeosu 59626, South Korea- 독성기전을 고려한 종 민감도 분포 기반 수계 및 토양 내 과불화옥탄술폰산(PFOS)의 예측 무영향 농도 산정

윤상규1ㆍ김우현2ㆍ정유진1ㆍ홍다희3ㆍ김지영1ㆍ장승환1,2,3ㆍ김태웅1,2,3ㆍ곽인실4ㆍ안진성1,2,3*

1한양대학교 대학원 스마트시티공학과

2한양대학교 ERICA 건설환경공학과

3한양대학교 대학원 건설환경시스템공학과

4전남대학교 해양융합과학과This article is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

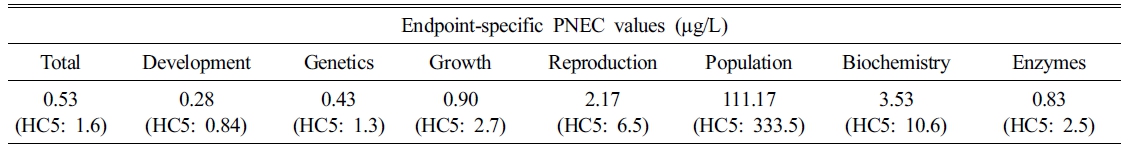

This study, estimates the predicted no effect concentration (PNEC) for the protection of organisms in aquatic and soil environments, considering the mode of action of Perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS). PNECs were derived using the species sensitivity distribution (SSD) approach to estimate the hazardous concentration for 5% of species (HC5), with applying assessment factors. Chronic toxicity data on PFOS were collected through the USEPA's ECOTOX database and literature reviews, and classified by toxicity endpoints. PNECs were then derived for each of seven toxicity endpoints that met the criteria for SSD fitting. For aquatic organisms, the PNEC for PFOS, based on all available chronic toxicity data, was determined to be 0.53 μg/L. The PNECs for development, genetics, enzymes, growth, reproduction, population, and biochemical biomarkers were 0.28, 0.43, 0.83, 0.90, 2.17, 111.17, and 3.53 μg/L, respectively. The lowest PNEC was observed when the toxic endpoint was set as development, which is considered to be due to the mode of action of PFOS, known to cause developmental toxicity by disrupting the endocrine system of organisms. For soil organisms, toxicity data were insufficient to estimate PNECs for individual endpoints, so all available data were used to estimate a PNEC of 0.75 mg/kg. Estimating PNECs that consider the mode of action of contaminants is expected to reduce the likelihood of underestimating protection levels for environmental contaminants. Additionally, this study highlights the need for ecotoxicological assessments for individual toxicity endpoints of emerging contaminants, including Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, in soil environments.

Keywords: Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, Emerging contaminants, Risk assessment, Ecotoxicologically acceptable concentration, Ecotoxicological assessment

과불화화합물(Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances; PFAS)은 탄소 골격에 여러 개의 불소 원자가 부착된 구조를 갖는 화학물질 그룹을 총칭한다(Glüge et al., 2020). 이러한 PFAS는 내방수성, 내접착성, 내열성과 같은 장점을 갖고 있어 1940년대에 발명된 이후 60년이상 섬유, 화장품, 요리 도구 등 광범위한 제품에서 사용되어 왔다(Xiao et al., 2020; Whitehead et al., 2021). 그 중 과불화옥탄술폰산(perfluorooctanesulfonic acid; PFOS)는 8개의 탄소 골격과 술폰산으로 이루어진 PFAS의 대표물질 중 하나로 지표수, 지하수 및 토양 등 다양한 환경매질에서 검출되고 있어(Xiao et al., 2015; Dhangar et al., 2020; Jarvis et al., 2021; Joo et al., 2021; Li et al., 2023), PFOS가 대상 환경에 서식하는 생물들에게 미치는 부정적인 영향에 대한 관심이 증가하고 있다(Saikat et al., 2013).

PFOS는 단백질에 강하게 결합할 수 있으며, 생물 내에 축적되어 호르몬 시스템에 영향을 미치는 내분비계 교란물질로 알려져 있다(Salvalaglio et al., 2010; Du et al., 2013). 따라서, 생물에 대한 PFOS의 축적은 발달(development), 대사(metabolism), 면역(immunity) 및 생식(reproduction) 등 다양한 독성영향을 유발할 수 있다(Qazi et al., 2009; Yue et al., 2020; Sant et al., 2021). 또한, PFOS는 열적, 화학적 안정성이 우수하여 가수분해, 생분해, 광분해에 대한 저항성이 높아 환경 내 자연 분해가 어려우며, 인체 내에서 평균적으로 5.4년의 긴 반감기를 가진 것으로 알려져 있어(Olsen et al., 2007), 안정적인 수계 및 토양 생태계의 관리와 대상 환경 내 생물들을 보호하기 위해 PFOS에 대한 생태위해성을 평가할 필요성이 있다.

이에 2009년 유엔 스톡홀름 협약(UN Stockholm Convention under Annex B)에서 잔류성 유기 오염물질(persistent organic pollutants; POPs)로 분류되어 전 세계적으로 단계적 퇴출 물질로 등재되었으며(UNEP, 2009), 미국, EU 등 많은 국가에서 PFOS를 신종오염물질로 규정하여 관리하고 있다(Liu et al., 2022). 그럼에도 불구하고 매년 많은 양의 PFOS가 수생 및 토양 생태계로 배출되고 있는 실정이다(Wang et al., 2017; Park et al., 2023).

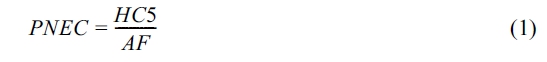

일반적으로 환경 내 오염물질의 생태위해성 평가 시, 대상 환경 내 생태독성학적으로 허용가능한 물질의 농도, 즉 생물들에게 독성영향이 나타나지 않는다고 예측되는 환경 중 오염물질의 농도인 예측 무영향 농도(predicted no effect concentration; PNEC)를 산정한다(Zheng et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2024). PNEC는 다양한 수계 및 토양 생물들에 대한 오염물질의 생태독성자료를 수집하고, 종 민감도 분포(species sensitivity distribution; SSD)를 활용하여 전체 생물종의 95%를 보호할 수 있는 수준의 농도인 5% hazardous concentration (HC5)을 도출한 후, 도출된 HC5의 불확실성을 보정하기 위한 평가계수(assessment factor; AF)를 적용하여 산정할 수 있다(Lee et al., 2020, Zheng et al., 2024).

PNEC 산정을 위한 SSD의 활용 시 사용되는 다양한 생물들에 대한 생태독성자료는 일반적으로 다양한 독성종말점 별 생태독성실험 결과를 모두 혼합하여 활용하거나(Kwak et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2022; Razak et al., 2023), 생태독성학의 전통적인 독성종말점인 생존(survival), 성장(growth) 및 발달에 대한 생태독성실험 결과만을 활용한다(Jin et al., 2014). 그러나, 이처럼 대상오염물질의 주요 독성기전을 고려하지 않고 SSD를 도시하는 경우, 도출된 HC5 및 PNEC가 과소평가될 개연성이 있다. Jin et al. (2014)은 중국 지표수 내 nonylphenol에 대한 생태위해성 평가를 위해 생존, 성장, 생식, 생화학(biochemistry) 및 분자생물학(molecular biology)적 인자를 독성종말점으로 한 생태독성자료를 수집하여 PNEC를 산정한 바 있으며, 수생생물인 경골어류의 번식 및 생식력을 감소시킨다고 알려진 nonylphenol의 주요 독성기전과 유사하게 독성종말점이 생식인 경우에 가장 낮은 PNEC를 나타냄을 확인했다. Liu et al. (2016)은 수계 내 diethylhexyl phthalate (DEHP)에 대한 수생생물 보호 수준을 평가하기 위해 생존, 성장, 발달, 생식, 생화학 및 분자생물학적 인자를 독성종말점으로 한 생태독성자료를 수집하여 독성종말점 별 PNEC를 산정한 바 있으며, DEHP의 주요 독성기전인 생식의 경우에 가장 낮은 PNEC를 나타냄을 확인했다. 따라서 생물종에 대한 오염물질의 독성기전을 고려한 PNEC 산정은 대상 환경 내 오염물질 보호수준의 과소평가 개연성을 해소할 수 있을 것으로 판단되므로, 대상 오염물질이 생물에게 미치는 주요 독성기전을 고려한 생태독성자료의 수집 및 분석을 통해, 보다 정확하고 신뢰성 있는 PNEC를 산정할 필요성이 있다. 최근 Zhang et al. (2024)은 수계 생물에 대한 PFOS 독성종말점 별 생태독성 실험 결과를 활용하여 SSD 도시를 통해 PNEC를 산정한 바 있으나 토양 생물에 대한 SSD 기반 PFOS의 PNEC 산정은 수행된 바 없다.

본 연구의 목적은 수계 및 토양 생물에 대한 PFOS의 독성기전을 고려하여 SSD를 기반으로 생태독성학적으로 허용가능한 PFOS의 농도인 PNEC를 산정하는 것이다. 이를 위해 수계 및 토양 생물들에 대한 PFOS의 생태독성자료를 수집하고 독성종말점 별로 분류했다. 또한, 전체 생태독성자료 및 독성종말점 별 SSD 도시를 통해 산정된 PFOS의 PNEC를 비교분석하여 수계 및 토양 생물들에 대한 PFOS의 독성 영향을 평가했다.

2.1.독성자료 수집

수계 생물의 PFOS에 대한 PNEC를 산정하기 위해 미국 환경 보호청(United States environmental protection agency; USEPA)에서 제공하는 ecotoxicology knowledgebase (ECOTOX)에서 생태독성 자료를 수집했다. 수집된 생태독성 자료는 용량-반응시험에서 실험군과 대조군 간 오염물질의 독성영향이 통계적 또는 생물학적으로 유의한 차이가 나타나지 않는 최고 노출농도인 무영향농도(no observed effect concentration; NOEC)이다. NOEC는 생물에게 유해한 영향을 미치지 않는 가장 높은 농도를 나타내며, 환경 보호를 위한 보수적 평가에 이점이 있다. 이후, 수집된 NOEC 자료를 독성실험 기간을 고려하여(Table 1) 급성 및 만성독성 자료로 구분했고(Wigger et al., 2019), 만성독성 자료만을 활용하여 수계 내 생태독성학적으로 허용가능한 PFOS의 농도를 산정했다. 이는 만성독성 자료가 급성독성 자료에 비해 대상 생물들에 대한 오염물질의 독성영향을 더 민감하게 나타내며, PFOS가 생물에게 미치는 장기적인 독성영향을 반영하기 때문이다(Smith et al., 2015; Park et al., 2020; Wigger et al., 2020; Chung et al., 2021).

토양 생물에 대한 PFOS 생태독성 자료는 ECOTOX에서 제공되지 않으므로, Web of science 에서 문헌조사를 수행하여 PFOS에 대한 NOEC를 수집했다. 검색 키워드는 “PFOS”, “perfluorooctanesulfonic acid”, “SSD”, “species sensitivity distribution”, “risk assessment”, “soil”, “NOEC”와 같은 키워드를 다양하게 조합하여 문헌을 검색했다. 그 결과 중복된 문헌을 제외하고 총 168개의 문헌이 검색됐으며, 토양 생물종 및 독성종말점 별로 구분하여 정리했다.

2.2.종 민감도 분포 도시 및 PNEC 산정

SSD는 다양한 생물들에 대한 오염물질의 생태독성자료를 사용하여 누적 확률 분포 곡선을 구축하고 HC5를 결정하는 방법이다(Sorgog et al., 2019; Naaz et al., 2023). SSD 도시를 위한 국내 최소 요건은 국립환경과학원에서 제시한 4분류군 5종 이상의 생물들에 대한 독성자료이며(National Institute of Environmental Research Notice, 2021), 본 연구에서는 국내 최소 요건을 만족하는 독성종말점 별 PFOS에 대한 만성 독성자료를 SSD tool box에 적용하여 SSD를 도시하고, 독성종말점 별 HC5를 도출했다. 한 종에 대한 NOEC가 여러 개인 경우 기하평균 값을 해당 종의 독성자료로 활용했다. 이후 도출된 HC5의 불확실성을 보정하기 위해 평가계수를 적용하여 PFOS에 대한 독성종말점 별 PNEC를 산정했다(식 1).

평가계수는 SSD 도시를 위한 독성자료가 충분하고 대상 수계에 대한 대표성이 있는 생물들에 대한 독성자료를 활용한 경우 1, 독성자료가 충분하지 않고 대상 수계에 대한 대표성이 부족한 경우에 5를 적용할 수 있다. 일반적으로 SSD 도시를 위한 최소 요건을 만족했으나 대표성이 부족한 경우에 평가계수 3을 적용할 수 있다(Lee et al., 2020).

|

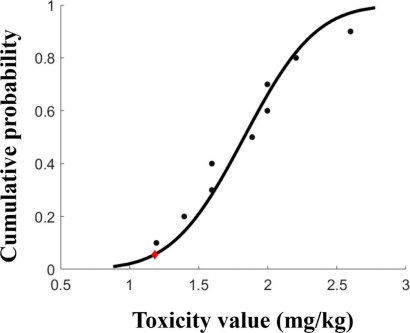

Table 1 Criteria for acute and chronic classification based on toxicity test duration for various species |

3.1.생태독성자료 수집 결과

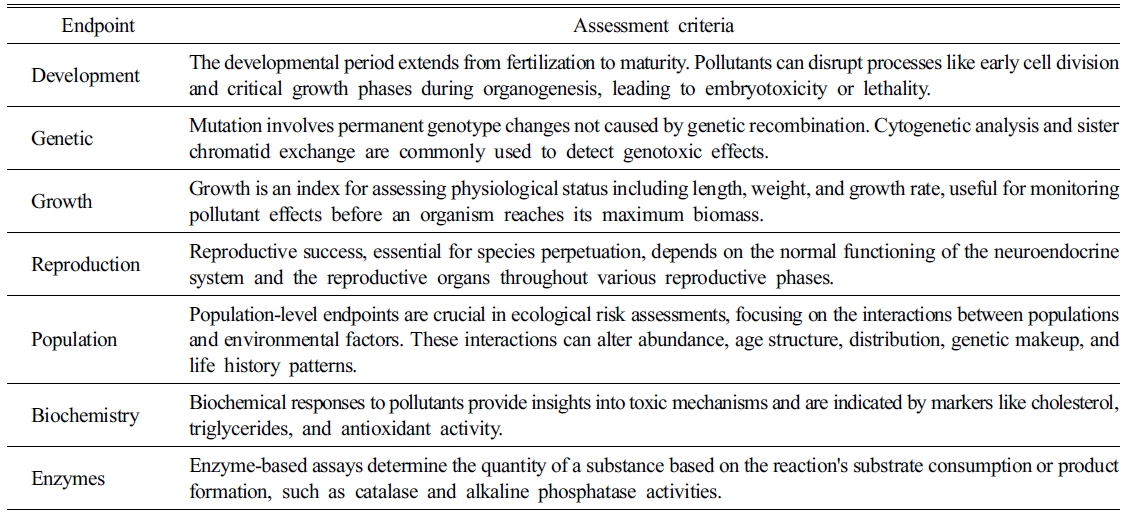

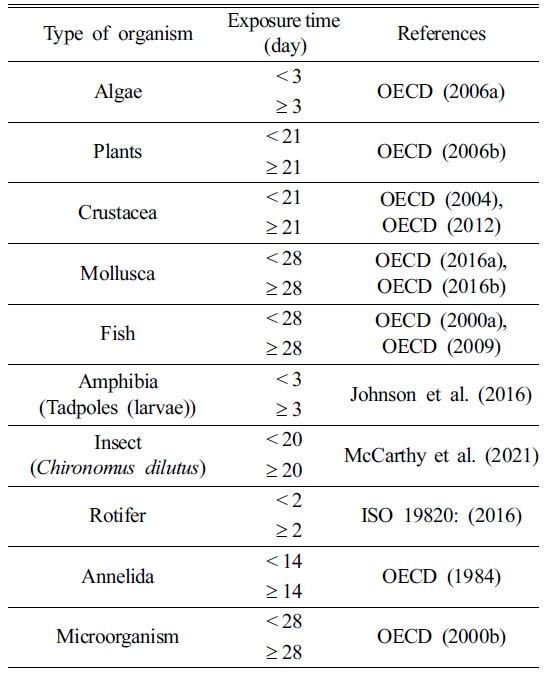

수계의 경우, ECOTOX로 수집된 총 2358개의 독성자료 중 만성독성자료는 652개로, 조류, 갑각류, 무척추동물, 어류를 포함하여 총 56종으로 이루어져 있다. 또한 652개의 만성독성자료는 발달, 유전(genetic), 성장, 생식, 개체군(population), 효소(enzymes) 및 생화학적 인자의 총 7개 독성종말점으로 구분되었으며, 이는 국립환경과학원에서 제시한 SSD 도시를 위한 최소 요건(4분류군 5종 이상)을 만족한다. 각각의 독성종말점에 대한 설명은 Table 2에 나타냈다.

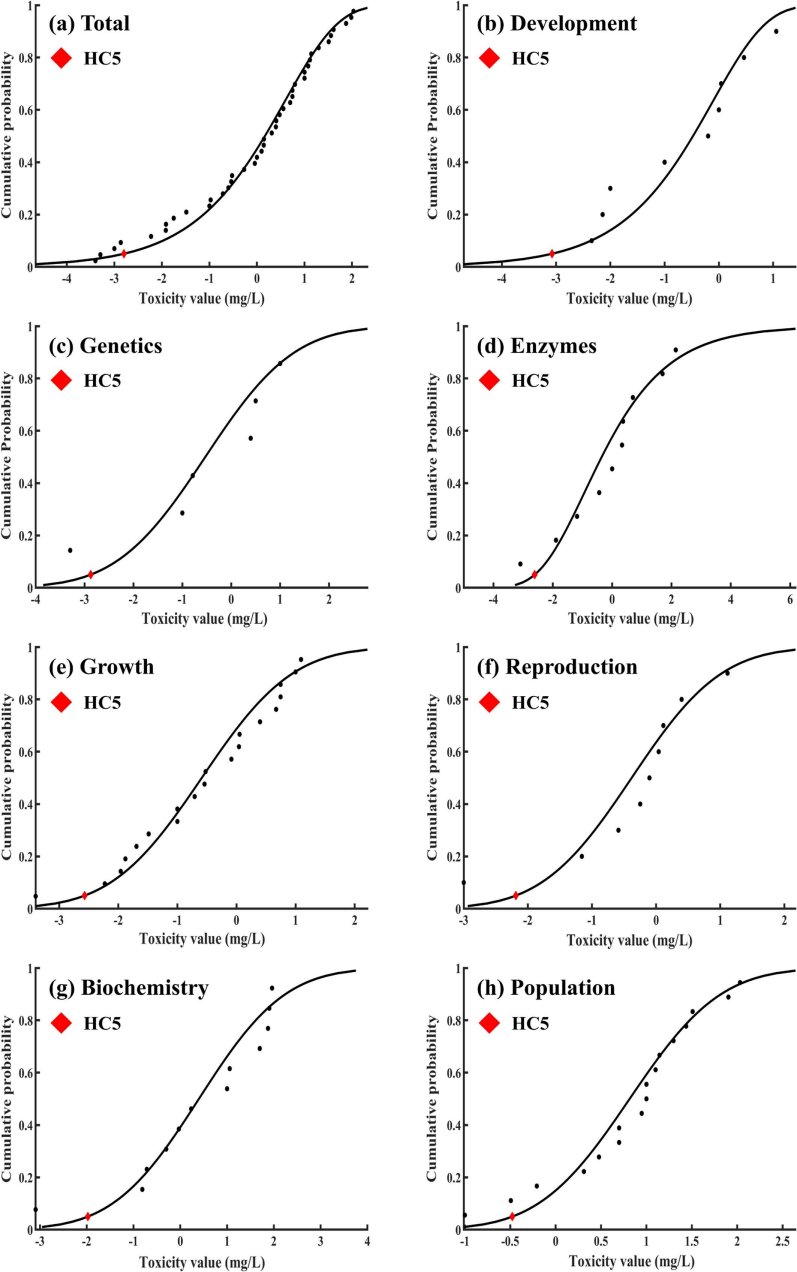

토양의 경우, Web of Science에서 문헌 조사를 통해 수집된 독성종말점 별 PFOS의 독성자료는 총 90개이다. 이 중 만성 독성자료는 26개로, 세 가지 분류군(무척추동물, 식물, 미생물)에서 총 11종으로 이루어져 있다. 수집된 토양 생물에 대한 독성종말점 별 PFOS의 만성 독성자료가 충분하지 않아 SSD 도시를 통한 HC5 도출 시 전체 만성 독성자료를 활용했으며, HC5를 활용한 PNEC 산정 시 평가계수는 5를 적용했다.

3.2.수계 생물에 대한 PFOS의 PNEC 산정 결과

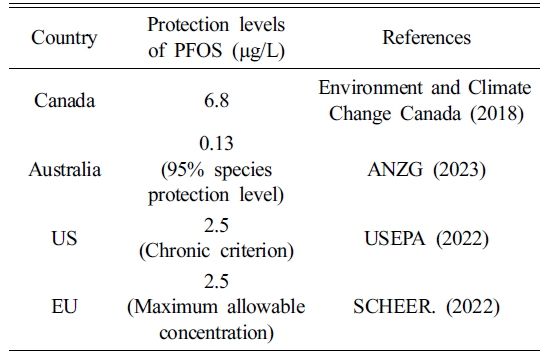

SSD 도시를 통해 산정된 수계 생물에 대한 PFOS의 HC5 및 평가계수를 활용한 PNEC 산정결과는 Fig. 1 및 Table 3에 나타냈다. 7가지 독성종말점 별 독성자료를 전부 활용한 경우 PNEC는 0.53 μg/L로 산정됐다. 다양한 국가 및 지역별 수계 내 PFOS에 대한 생물 보호 수준은 0.13 μg/L-6.8 μg/L이며(Table 4), 이와 같이 국가 및 지역별 수계마다 상이한 PFOS의 보호 수준이 도출되는 것은 대상 수계 내 서식하는 생물종, 노출 경로, 평가계수 및 평가 방법(e.g., HC5 (95%), HC1 (99%)) 등의 차이에 의해 발생할 수 있다. 또한, 전체 및 독성종말점 별 PNEC를 비교해 보았을 때, 독성종말점이 발달 및 유전인 경우 PNEC는 각각 0.28 μg/L 및 0.43 μg/L로 산정됐으며, 전체 독성자료를 활용하여 산정된 PNEC에 비해 낮은 PNEC가 관찰됐다. 이는 전체 독성자료를 활용하여 수계 생물을 보호하기 위한 생태독성학적 허용가능 PFOS의 농도를 산정하는 경우, 수계 생물에 대한 PFOS의 독성영향을 과소평가할 개연성이 있음을 의미하며, 생물에 대한 PFOS의 독성기전을 고려하여 대상 독성종말점을 기반으로 한 PNEC를 산정할 필요성이 있음을 나타낸다. Qiao et al. (2022)은 수계 생물들에 대한 tris(2-chloroethyl)phosphate (TCEP)의 독성종말점 별(생존, 발달, 생식) 생태독성 실험 결과를 수집하여 결합확률곡선(joint probability curves; JPCs)을 통한 TCEP의 생태 위해성 평가를 수행한 바 있다. 독성종말점이 생식인 경우, 가장 높은 생태위해성을 나타냈으며, 이는 생식과 관련된 다양한 유전자 및 단백질 합성 경로의 교란을 통해 생물의 생식능력을 감소시킬 수 있다고 알려진 TCEP의 독성기전에 의한 것으로 추정한 바 있다. Zhang et al. (2024)은 수계 생물에 대한 PFOS 독성종말점 별(성장 및 발달, 생식, 생존, 유전 및 생화학적 인자) 생태독성실험 결과(NOEC 및 10% effective concentration (EC10))를 수집하여 SSD 도시를 통한 PNEC를 산정한 바 있다(평가계수 1 적용). 전체 독성자료를 활용한 경우 PFOS의 PNEC는 3.02 μg/L으로 나타났으며, 발달 및 성장, 생식, 생존, 유전 및 생화학적 인자 각각 0.797 μg/L, 3.93 μg/L, 13.3 μg/L, 43.4 μg/L로 나타나 독성종말점이 발달 및 성장인 경우 가장 낮은 PNEC를 나타냄을 확인한 바 있다. 해당 문헌(Zhang et al., 2024)에서 산정된 PFOS의 PNEC와 본 연구에서 산정된 PNEC 산정결과를 비교해 볼 때, 본 연구에서는 보다 높은 수계 내 PFOS 보호수준을 나타냈다. 이는 PNEC 산정에 활용한 독성자료 및 평가계수의 영향으로 추정된다(독성자료로 NOEC만 사용, 평가계수 3 적용). 또한, 본 연구에서도 독성종말점이 발달인 경우, 가장 낮은 PNEC를 나타냈다. 이는 수계 생물의 발달에 독성영향을 발현할 수 있는 PFOS의 농도가 다른 종말점에 비해 낮다는 것, 즉 PFOS의 주요 독성기전이 발달 독성일 수 있다는 것을 의미한다. Toft et al. (2016)은 PFOS가 태반을 통과하여 발달 중인 태아에 독성영향을 미칠 수 있다고 보고한 바 있다. Sant et al. (2017)은 zebrafish 배아를 대상으로 한 PFOS 생태독성실험을 수행한 바 있으며, PFOS의 노출로 인해 배아의 크기가 감소하고, 췌장의 길이 및 형태를 비정상적으로 변형시켜 배아의 발달과정에 독성영향을 미칠 수 있음을 확인한 바 있다. Ankley et al. (2009a)은 양서류(Rana pipiens)를 대상으로 배아에서 최종 변태기간까지 생존 및 발달에 대한 PFOS의 독성영향을 확인한 바 있다. 10 mg/L의 PFOS를 노출한 경우, 약 2주 이내에 생물의 90% 이상이 사망했으나, 10 mg/L 미만의 농도에서는 PFOS가 대상 생물의 생존에 영향을 미치지 않음을 확인했으며(90% 이상 생존), 발달의 경우 3 mg/L의 PFOS의 노출 시 배아의 성장 기간 지연 및 갑상선 호르몬 농도 감소의 영향을 나타냈다. 이는 PFOS가 생물의 성장에 비해 발달에 더 높은 독성영향을 나타낼 수 있다는 것을 의미한다. 또한, Ankley et al. (2009b)은 Pimephales promelas를 활용하여 27일간의 PFOS 생태독성실험을 수행한 바 있으며, PFOS가 대상 생물의 성장 및 생존에 비해 생식 및 발달과정에 더 높은 독성영향을 미칠 수 있음을 확인한 바 있다. 결과적으로, 독성종말점이 발달인 경우 PFOS에 대한 가장 낮은 PNEC를 나타내는 것은, 생물 내에 축적되어 호르몬 시스템의 교란을 통해 생물의 발달과정에 독성영향을 미칠 수 있다고 알려진 PFOS의 주요 독성기전에 의한 것으로 판단된다.

3.3.토양 생물에 대한 PFOS의 PNEC 산정 결과

토양 생물에 대한 PFOS의 전체 만성 독성자료를 활용하여 산정된 HC5는 3.77 mg/kg으로 나타났으며(Fig. 2), 수집된 토양 생물에 대한 PFOS의 만성 독성자료가 제한적이므로, 전체 만성 독성자료를 활용하여 산정된 결과와 독성종말점 별로 산정된 결과간의 비교는 수행되지 않았다.

보고된 문헌에 따르면(Chen et al., 2014; Guo et al., 2016), 토양 생물인 Caenorhabditis elegans에 대한 PFOS의 독성이 행동 억제(behavioral inhibition), 신경독성(neurotoxicity), 산화스트레스 촉진을 통한 발달독성을 일으킬 수 있음을 확인한 바 있으므로, 향후 토양 생물에 대한 PFOS 보호 수준 산정을 위해서 다양한 토양 생물종에 대한 독성종말점 별 독성자료를 생산 및 확보할 필요성이 있다.

본 연구에서 산정된 토양 내 생태독성학적 허용가능 PFOS의 농도는 0.75 mg/kg이다. Cooperative research centre for contamination assessment and remediation of the environment (creCARE, Australia)에서는 토양 생물 총 7종 (무척추동물, 식물, 미생물)에 대한 PFOS의 만성 독성실험 결과를 수집하여 호주 토양 내 PFOS의 보호 수준을 산정한 바 있으며, 그 결과 국립공원지역의 95% 생물종 보호수준에서 6.6 mg/kg으로 나타났다(crcCARE, 2017). USEPA에서는 지하수 및 지표수 오염을 방지하기 위한 PFOS의 지역 스크리닝 수준(regional (soil) screening level; RSL)을 0.378 μg/kg으로 산정한 바 있으며, 인간 건강을 보호하기 위한 토양 내 PFOS의 스크리닝 수준은 1.26 mg/kg으로 산정한 바 있다. 또한 호주 및 뉴질랜드의 경우, 인간 건강을 보호하기 위한 PFOS의 수준은 정원 및 주거용 토양에서 10 μg/kg이었으며, 캐나다의 경우 농업 및 주거지역에서 2.1 mg/kg으로 토양 내 PFOS에 대한 보호수준을 산정한 바 있다(Liu et al., 2022). 이처럼 토양 내 PFOS의 보호수준이 국가 또는 지역마다 상이한 것은 서로 다른 대상 토양 내 생물종, 노출 경로, 평가계수, 평가 방법(e.g., HC5 (95%), HC1 (99%)) 등 다양한 고려사항의 차이에 의해 발생할 수 있다. 이를 고려할 때, 대상 지역 별 토양 환경 및 특성에 맞는 현장 특이적(site-specific)인 생태독성학적 허용가능 PFOS 농도 산정이 필요하다.

|

Fig. 1 Species sensitivity distribution based on NOEC of PFOS by toxic endpoints for aquatic organisms. |

|

Fig. 2 Species sensitivity distribution of PFOS for soil organisms. |

|

Table 3 PNEC of PFOS for aquatic species by toxic endpoints determined from species sensitivity distribution |

Assessment factor: 3 |

|

Table 4 Protection levels of PFOS in aquatic environments in different countries |

본 연구에서는 다양한 생물들에 대한 PFOS의 독성기전을 고려하여 SSD를 기반으로 독성종말점 별 생태독성학적 허용가능 농도(PNEC)를 산정했다. 그 결과, 수계 생물에 대한 PNEC는 독성종말점이 발달인 경우 0.28 μg/L로 가장 낮은 값을 나타냈다. 이와 같은 결과는 수계 생물들에 대한 PFOS의 주요 독성기전이 발달독성임을 시사하며, 독성기전을 고려하지 않는 경우, 산정된 보호수준이 과소평가될 개연성이 있음을 나타낸다. 따라서, 보다 신뢰성 있는 대상 환경 내 PFOS 관리 수준을 수립하기 위해서는 독성기전을 고려한 평가가 필요하다. 또한, 토양 생물에 대한 PNEC 산정 결과는 전체 만성 독성자료를 활용한 경우 0.75 mg/kg으로 산정됐다. 토양 생물에 대한 PFOS의 만성 독성자료가 제한적이므로, 향후 토양 내 독성기전을 고려한 생태독성학적 허용가능 PFOS 농도를 산정하기 위해서는 다양한 토양 생물종에 대한 종말점별 독성자료를 추가적으로 확보하는 것이 필요하다.

This work was supported by the Korea Environmental Industry & Technology Institute (KEITI) through the Aquatic Ecosystem Conservation Research Program, funded by the Korea Ministry of Environment (MOE)(2021003050001), the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the ministry of Science and ICT (MSIT) (NRF-2022R1F1A1076510).

- 1. Ankley, G.T., Kuehl, D.W., Kahl, M.D., Jensen, K.M., Butterworth, B.C., and Nichols, J.W., 2009a. Partial life-cycle toxicity and bioconcentration modeling of perfluorooctanesulfonate in the northern leopard frog (Rana pipiens). Environ. Toxicol. Chem., 23(11), 2745-2755.

-

- 2. Ankley, G.T., Kuehl, D.W., Kahl, M.D., Jensen, K.M., Linnum, Ann, Leino, R.L., and Villeneuve, D.A., 2009b, Reproductive and developmental toxicity and bioconcentration of perfluorooctanesulfonate in a partial life-cycle test with the fathead minnow (Pimephales promelas), Environ. Toxicol. Chem., 24(9), 2316-2324,

-

- 3. ANZG (Australian and New Zealand Governments), 2023, Toxicant default guideline values for aquatic ecosystem protection: Perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) in freshwater, Australian and New Zealand Guidelines for Fresh and Marine Water Quality, Australian Government Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water, Canberra, ACT, Australia, 15p.

- 4. Chen, N., Li, J., Li, D., Yang, Y., and He, D., 2014, Chronic exposure to perfluorooctane sulfonate induces behavior defects and neurotoxicity through oxidative damages, in vivo and in vitro, PloS one., 9(11), e113453.

-

- 5. Chung, J., Hwang, D.-S., Park, D.-H., An, Y.J., Yeom, D.-H., Park, T.-J., Choi, J., and Lee, J.-H., 2021, Derivation of acute copper biotic ligand model-based predicted no-effect concentrations and acute-chronic ratio, Sci. Total Environ., 780, 146425.

-

- 6. CRCCARE (Cooperative research centre for contamination assessment and remediation of the environment), 2017. Assessment, management and remediation guidance for perfluorooctanesulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) Part 3 – ecological screening levels. Cooperative Research Centre for Contamination Assessment and Remediation of the Environment, Newcastle.

- 7. Dhangar, D. and Kumar, M., 2021. Perfluorooctanesulfonate (PFOS), Its occurrence, fate, transport and removal in various environmental media: A review. Contaminants in Drinking and Wastewater Sources, 405-436.

-

- 8. Du, G., Hu, J., Huang, H., Qin, Y., Han, X., Wu, D., Song, L., Xia, Y., and Wang, X., 2013, Perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) affects hormone receptor activity, steroidogenesis, and expression of endocrine‐related genes in vitro and in vivo, Environ. Toxicol. Chem., 32(2), 353-360.

-

- 9. ECOTOX , https://cfpub.epa.gov/ecotox/ [23.11.29]

- 10. Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2018, Federal Environmental Quality Guidelines: Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS), Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999, Ottawa, Canada, 13p.

- 11. Glüge, J., Scheringer, M., Cousins, I.T., DeWitt, J.C., Goldenman, G., Herzke, D., Lohmann, R., Ng, C. A., Trier, X., and Wang, Z., 2020, An overview of the uses of per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts, 22(12), 2345-2373.

-

- 12. Guo, X., Li, Q., Shi, J., Shi, L., Li, B., Xu, A., Zhao, G., and Wu, L., 2016, Perfluorooctane sulfonate exposure causes gonadal developmental toxicity in Caenorhabditis elegans through ROS-induced DNA damage, Chemosphere, 155, 115-126.

-

- 13. ISO (International Organization for Standardization), 2016, Water quality — Determination of the acute toxicity to the marine rotifer Brachionus plicatilis, International Organization for Standardization, Geneva, 13p.

- 14. Jarvis, A.L., Justice, J.R., Elias, M.C., Schnitker, B., and Gallagher, K., 2021, Perfluorooctane sulfonate in US ambient surface waters: a review of occurrence in aquatic environments and comparison to global concentrations, Environ. Toxicol. Chem., 40(9), 2425-2442.

-

- 15. Jin, X., Wang, Y., Jin, W., Rao, K., Giesy, J. P., Hollert, H., Richardson, K.L., and Wang, Z., 2014, Ecological risk of nonylphenol in china surface waters based on reproductive fitness, Environ. Sci. Technol., 48(2), 1256-1262.

-

- 16. Johnson, M.S., Aubee, C., Salice, C.J., Leigh, K.B., Liu, E., Pott, U., and Pillard, D., 2016, Areview of ecological risk assessment methods for amphibians: Comparative assessment of testing methodologies and available data, Integr. Environ. Asses. Manag., 13(4), 601-613.

-

- 17. Sorgog, K. and Kamo, M., 2019, Quantifying the precision of ecological risk: Conventional assessment factor method vs. species sensitivity distribution method, Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf., 183, 109494.

-

- 18. Joo, G., Kim, Y., Kim, G., Song, J., Lee, M., Choe, J.K., and Choi, Y., 2021, Perfluorochemicals in Korean wastewater treatment plants: implications on sources and monitoring, KSCE J. Civ. Eng., 25, 1931-1938.

-

- 19. Kwak, J.I., Lee, T.-Y., Seo, H., Kim, D., Kim, D., Cui, R., and An, Y.-J., 2020, Ecological risk assessment for perfluorooctanoic acid in soil using a species sensitivity approach, J. Hazard. Mater., 382, 121150.

-

- 20. Lee, B., Lee, B., Kim, P., and Yoon, H., 2020, Ecological risk assessment of lead and arsenic by environmental media, J. Environ. Health Sci., 46(1), 1-10.

-

- 21. Li, H. and Koosaletse-Mswela, P., 2023, Occurrence, fate, and remediation of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in soils: a review, Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health., 34, 100487.

-

- 22. Li, Q., Wang, T., Zhu, Z., Meng, J., Wang, P., Zhang, Y., Zhou, Y., Song, S., Lu, Y., Yvette, B., Suriyanarayanan, S. Zhang, Y., Zhou, Y., Song, S., Lu, Y., and Yvette, B., 2017, Using hydrodynamic model to predict PFOS and PFOA transport in the Daling River and its tributary, a heavily polluted river into the Bohai Sea, China, Chemosphere, 167, 344-352.

-

- 23. Liu, N, Wang, Y., Yang, Q., Lv, Y., Jin, X., Giesy, J.P., and Johnson, A.C., 2016, Probabilistic assessment of risks of diethylhexyl phthalate (DEHP) in surface waters of China on reproduction of fich, Environ. Pollut., 213, 482-488.

-

- 24. Liu, Y., Bahar, M.M., Samarasinghe, S.V.A.C., Qi, F., Carles, S., Richmond, W.R., Dong, Z., and Naidu, R., 2022, Ecological risk assessment for perfluorohexanesulfonic acid (PFHxS) in soil using species sensitivity distribution (SSD) approach, J. Hazard. Mater., 439, 129667.

-

- 25. McCarthy, C.J., Roark, S.A., WRIGHT, D., O'Neal, K., Muckey, B., Stanaway, M., Reserts, J.N., Field, J.A., Anderson, T.A., and Salice, C.J., 2021. Toxicological response of Chironomus dilutus in single-chemical and binary mixture exposure experiments with 6 perfluoralkyl substances. Environ. Toxicol. Chem., 40(8), 2319-2333.

-

- 26. Naaz, T., Kumar, A., Vempaty, A., Singhal, N., Pandit, S., Gautam, P., and Jung, S.P., 2023, Recent advances in biological approaches towards anode biofilm engineering for improvement of extracellular electron transfer in microbial fuel cells, Environ. Eng. Res., 28(5), 220666.

-

- 27. National Institute of Environmental Research Notice No. 2021-13, 2021, Regulations on specific methods of chemical risk assessment, etc. [Appendix 4] Minimum data requirements for using species sensitivity distribution (related to Article 6, Paragraph 6, Item 2).

- 28. OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), 1984, Test No. 207: Earthworm, Acute Toxicity Tests, OECD Publishing, Paris.

- 29. OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), 2000a, Test No. 215: Fish, Juvenile Growth Test, OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 2, OECD Publishing, Paris.

- 30. OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), 2000b, Test No. 216: Soil Microorganisms: Nitrogen Transformation Test, OECD Publishing, Paris.

- 31. OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), 2004, Test No. 202: Daphnia sp. Acute Immobilisation Test, OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 2, OECD Publishing, Paris.

- 32. OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), 2006a, OECD guidelines for the testing of chemicals: Freshwater alga and cyanobacteria, growth inhibition test, OECD Publishing, Paris, 25 p.

- 33. OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), 2006b, Test No. 227: Terrestrial plant test: Vegetative vigour test, OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 2, OECD Publishing, Paris, 21p.

- 34. OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), 2009, Test No. 230: 21-day Fish Assay: A Short-Term Screening for Oestrogenic and Androgenic Activity, and Aromatase Inhibition, OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 2, OECD Publishing, Paris.

- 35. OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), 2012, Test Guideline No. 211: Daphnia magna Reproduction Test, OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 2, OECD Publishing, Paris.

- 36. OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), 2016a, Test No. 243: Lymnaea stagnalis Reproduction Test, OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 2, OECD Publishing, Paris.

- 37. OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), 2016b, Test No. 242: Potamopyrgus antipodarum Reproduction Test, OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 2, OECD Publishing, Paris.

- 38. Olsen, G.W., Burris, J.M., Ehresman, D.J., Froehlich, J.W., Seacat, A.M., Butenhoff, J.L., and Zobel, L.R., 2007, Half-life of serum elimination of perfluorooctanesulfonate, perfluorohexanesulfonate, and perfluorooctanoate in retired fluorochemical production workers, Environ. Health Perspect., 115(9), 1298-1305.

-

- 39. Park, J. and Kim, S. D., 2020, Derivation of predicted no effect concentrations (PNECs) for heavy metals in freshwater organisms in Korea using species sensitivity distributions (SSDs), Minerals, 10(8), 697.

-

- 40. Park, S.-B. and Jang, Y.-Y., 2023, A study on the emission of fluorine-based chemicals and the detection of perfluorooctane sulfonic acids(PFOS) ans perfluorooctanic acids (PFOA) in domestic main rivers, J. Korea Org. Resour. Recycl. Assoc., 31(2), 5-18.

-

- 41. Qazi, M.R., Bogdanska, J., Butenhoff, J.L., Nelson, B.D., DePierre, J.W., and Abedi-Valugerdi, M., 2009, High-dose, short-term exposure of mice to perfluorooctanesulfonate (PFOS) or perfluorooctanoate (PFOA) affects the number of circulating neutrophils differently, but enhances the inflammatory responses of macrophages to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in a similar fashion, Toxicology, 262(3), 207-214.

-

- 42. Qiao, Y., Liu, D., Feng, C., Liu, N, Wang, J., Yan, Z., and Bai, Y., 2022, Ecological risk assessment for tris(2-chloroethyl) phosphate to freshwater organisms, Front. Environ. Sci., 10, 963918.

-

- 43. Razak, M.R., Aris, A.Z., Zainuddin, A.H., Yusoff, F.M., Yusof, Z.N.B., Kim, S.D., and Kim, K.W., 2023, Acute toxiciy and risk assessment of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctanesulfonate (PFOS) in tropical cladocerans Moina micrura, Chemosphere, 313, 137377.

-

- 44. Saikat, S., Kreis, I., Davies, B., Bridgman, S., and Kamanyire, R., 2013, The impact of PFOS on health in the general population: a review, Environ. Sci.: Process. Impacts, 15(2), 329-335.

-

- 45. Salvalaglio, M., Muscionico, I., and Cavallotti, C., 2010, Determination of energies and sites of binding of PFOA and PFOS to human serum albumin, J. Phys. Chem. B, 114(46), 14860-14874.

-

- 46. Sant, K.E., Annunziato, K., Conlin, S., Teicher, G., Chen, P., Venezia, O., Downes, G.B., Park, Y., and Timme-Laragy, A.R., 2021, Developmental exposures to perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) impact embryonic nutrition, pancreatic morphology, and adiposity in the zebrafish, Danio Rerio, Environ. Pollut., 275, 116644.

-

- 47. Sant, K.E., Jacobs, H.M., Borofski, K.A., Moss, J.B., and Timme-Laragy, A.R., 2017, Embryonic exposures to perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) disrupt pancreatic organogenesis in the zebrafish, Danio rerio, Environ. Pollut., 220, 807-817.

-

- 48. SCHEER (Scientific Committee on Health, Environmental and Emerging Risks), 2022, Final Opinion on Draft Environmental Quality Standards for Priority Substances under the Water Framework Directive - PFAS, European Commission, 25 p.

- 49. Smith, K.S., Balistrieri, L.S., and Todd, A.S., 2015, Using biotic ligand models to predict metal toxicity in mineralized systems, Appl. Geochem., 57, 55-72.

-

- 50. Species Sensitivity Distribution (SSD) Toolbox, https://www.epa. gov/comptox-tools/species-sensitivity-distribution-ssd-toolbox [23.12.12]

- 51. Toft, G., Jönsson, B.A.G., Bonde, J.P., N©ªrgaard-Pedersen, B., Hougaard, D.M., Cohen, A., Lindh C.H., Ivell, R., Anandlvell, R., and Lindhard, M.S., 2015, Perfluorooctane sulfonate concentrations in amniotic fluid, biomarkers of fetal leydigcell function, andcryptorchidism and hypospadias in danish boys (1980-1996), Environ. Health. Perspect., 124(1), 151-156.

- 52. UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme), 2009, Report of the Conference of the Parties of the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants on the work of its fourth meeting, UNEP/POPS/COP.4/38, Geneva, Switzerland, United Nations Environment Programme.

- 53. USEPA (United States Environmental Protection Agency), 2024, Final Recommended Aquatic Life Criteria and Benchmarks for Select PFAS, EPA, Washington, DC, 4p.

- 54. Wang, Z., Boucher, J.M., Scheringer, M., Cousins, I.T., and Hungerbuhler, K., 2017, Toward a comprehensive global emission inventory of C4–C10 perfluoroalkanesulfonic acids (PFSAs) and related precursors: focus on the life cycle of C8-based products and ongoing industrial transition, Environ. Sci. Technol., 51(8), 4482-4493.

-

- 55. Wang, Z., Li, Z., Lou, Q., Pan, J., Wang, J., Men, S., and Yan, Z., 2024, Ecological risk assessment of 50 emerging contaminants in surface water of the Greater Bay Area, China, Sci. Total Environ., 907, 168105.

-

- 56. Whitehead, H.D., Venier, M., Wu, Y., Eastman, E., Urbanik, S., Diamond, M.L., Shalin, A., Schwartz-Narbonne, H., Bruton, T.A., Blum, A., Wang, Z., Green, M., Tighe, M., Wilkinson, J.T., McGuinness, S., and Peaslee, G.F., 2021, Fluorinated compounds in North American cosmetics, Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett., 8(7), 538-544.

-

- 57. Wigger, H., Kawecki, D., Nowack, B., and Adam, V., 2020, Systematic consideration of parameter uncertainty and variability in probabilistic species sensitivity distribution, Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag., 16(2), 211-222.

-

- 58. Xiao, F., Sasi, P.C., Yao, B., Kubátová, A., Golovko, S.A., Golovko, M.Y., and Soli, D., 2020, Thermal stability and decomposition of perfluoroalkyl substances on spent granular activated carbon, Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett., 7(5), 343-350.

-

- 59. Xiao, F., Simcik, M.F., Halbach, T.R., and Gulliver, J.S., 2018, Perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoate (PFOA) in soils and groundwater of a U.S. metropolitan area: migration and implications for human exposure, Water Res., 72, 64-74.

-

- 60. Yue, Y., Li, S., Qian, Z., Pereira, R.F., Zhang, Z., Peng, Y., Park, Y., Lee, J., Doherty, J.J., Clark, J.M., Timme-Laragy, A.R., and Park, Y., 2020, Perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) and perfluorobutanesulfonic acid (PFBS) impaired reproduction and altered offspring physiological functions in Caenorhabditis elegans, Food Chem. Toxicol., 145, 111695.

-

- 61. Zhang, J., Tao, H., Shi, J., Ge, H., Li, B., Wang, Y., Zhang, M., and Li, X., 2024, Deriving aquatic PNECs of endocrine disruption effects for PFOS and PFOA by combining species sensitivity weighted distributions and adverse outcome pathway networks, Chemosphere, 364, 140583.

-

- 62. Zheng, Z.-Y. and Ni, H.-G., 2024, Predicted no-effect concentration for eight PAHs and their ecological risks in seven major river systems of China, Sci. Total Environ., 906, 167590.

-

This Article

This Article

-

2024; 29(5): 27-36

Published on Oct 31, 2024

- 10.7857/JSGE.2024.29.5.027

- Received on Oct 7, 2024

- Revised on Oct 17, 2024

- Accepted on Oct 22, 2024

Services

Services

Shared

Correspondence to

Correspondence to

- Jinsung An

-

1Department of Smart City Engineering, Hanyang University, Ansan 15588, South Korea

2Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Hanyang University, Ansan 15588, South Korea

3Department of Civil and Environmental System Engineering, Hanyang University, Ansan 15588, South Korea - E-mail: jsan86@hanyang.ac.kr