- Assessment of Radon Tracer for DNAPL Characterization Within the Groundwater Through Push-pull Tests

Jaeyeon KimㆍYe Ji KimㆍJi-Young BaekㆍJun-Young ShinㆍSeong-Sun LeeㆍKang-Kun Lee*

School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Seoul National University, Seoul 08826, Republic of Korea

- 주입-양수 시험을 통한 지하수 내 DNAPL 특성화 시 라돈 추적자 평가

김재연ㆍ김예지ㆍ백지영ㆍ신준영ㆍ이성순ㆍ이강근*

서울대학교지구환경과학부

This article is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Dense non-aqueous phase liquids (DNAPLs) pose significant threats to the ecosystem and human health due to their persistence and migration in groundwater. This study evaluates the application of radon as a natural tracer for identifying DNAPL distribution within a bedrock aquifer, where traditional radon deficiency principles may be compromised by factors such as high permeability fractures. For this, two push-pull tests were conducted. The results from the inter-well test highlighted that radon behavior was dominated by mixing processes with background water, indicating that the radon tracer can act similarly to the conservative tracer without contamination of DNAPL. Conversely, the single-well test indicated that radon concentrations were influenced by phase partitioning with TCE within a certain radial range, suggesting the presence of entrapped TCE within this particular area. While this heterogeneous existence of TCE was interpreted to induce the non-conventional breakthrough curve (BTC) patterns, heterogeneity of the flow field was also determined to be a potential reason. Overall, the findings confirm that radon can be effectively utilized as a tracer for monitoring DNAPL distribution within bedrock aquifers, considering the main influential physical processes, including phase partitioning with TCE or mixing processes with other water bodies.

Keywords: Radon, Dense non-aqueous phase liquids, Single-well push-pull test, Inter-well push-pull test, Bedrock aquifer

Dense non-aqueous phase liquids (DNAPLs) pose a significant threat to ecosystems and human health (Barrio-Parra et al., 2021; Engelmann et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2024). These contaminants are commonly found in industrial areas and, due to their low solubility in water and higher density than water, DNAPLs can migrate extensively below the groundwater table, contaminating multiple aquifers (Berkowitz, 2002; Lerner et al., 2003). The DANPLs can migrate through porous media by pressure gradient and underlain fractured rock media, especially high permeable fractures. Chlorinated solvents, such as tetrachloroethylene (PCE) and trichloroethylene (TCE), are particularly risky to human health because they persist in groundwater, a crucial water resource. Therefore, understanding the migration and mixing processes of these hazardous compounds is critical for effective management, which can enhance water security and inform remediation plans.

Radon, a naturally occurring tracer in groundwater, has been used as a partitioning tracer to locate and quantify NAPL saturation in aquifers. Radon is part of the uranium-238 decay series and has a short half-life of 3.83 days. In the presence of NAPLs, radon concentration surrounding the contaminated source area is reduced, as radon is displaced from the groundwater into the NAPL, a phenomenon known as radon deficiency (Briganti et al., 2024; Mattia et al., 2023; Semprini et al., 2000). This principle can also be applied in DNAPL-contaminated zones (Barrio-Parra et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2024). However, the use of radon as a tracer has limitations; it is sensitive to sudden environmental changes, such as mixing processes, making it not solely influenced by the partitioning to DNAPL. Moreover, the radon can not be used as tracer according to the bedrock characteristics. Therefore, to evaluate the applicability of radon as a natural tracer for delineating DNAPL characteristics, it is crucial to consider specific field testing methods.

One of the most effective methods for investigating subsurface contamination is the push-pull test (Istok, 2012). The principle involves spiking water with a tracer, pumping it into the well, and then extracting water from the same well or adjacent well. Tracer concentrations are measured during the test from the pumped water, generating a breakthrough curve (BTC). Specifically, push-pull partitioning tracer tests have been used to quantify NAPL saturation (Brusseau et al., 1999; Istok et al., 1999; Jin et al., 2024). An injection solution containing both partitioning and conservative tracers is injected into an aquifer and extracted from the same well (single-well push-pull test) or another well (inter-well push-pull test). Radon has been utilized as a partitioning tracer in several studies (Davis et al., 2002, 2003, 2005). However, previous studies have primarily been conducted in laboratory settings or as single-well push-pull tests exclusively in NAPL-contaminated zones.

This research describes and discusses the site characteri- zation of a DNAPL-contaminated groundwater zones based on the radon tracer. Characteristically, the groundwater wells in the study site are located in a bedrock aquifer. As DNAPLs migrate through networks of highly permeable fractures, the transport process can be influenced by factors which potentially violate the radon deficiency principle. Therefore, the primary goal of this study is to evaluate the application of radon as a reliable tool to trace DNAPL distribution along the groundwater flow within bedrock aquifers. To achieve this, two pumping tests were conducted to investigate the dominant physical processes affecting radon concentrations: (1) an inter-well push-pull test in the non-DNAPL contaminated zone, and (2) a single-well push-pull test in the DNAPL-contaminated zone. Based on these tests, this study provides approaches that address the limitations of radon tracers, thereby improving their application in DNAPL-contaminated areas.

2.1. Study area

The study area is located at the Namdong industrial complex, Incheon, South Korea. While this place now stands as a representative industrial complex, before the 1980’s it consisted of salt pans and mud flats. After the Capital Region Plan had been announced, a land reclamation project was conducted from 1985 to 1997. Various factories were positioned thereafter which now all make up the industrial complex (Incheon Metropolitan City Museum, 2020).

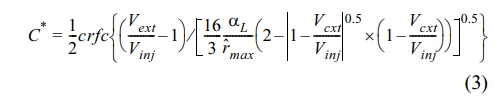

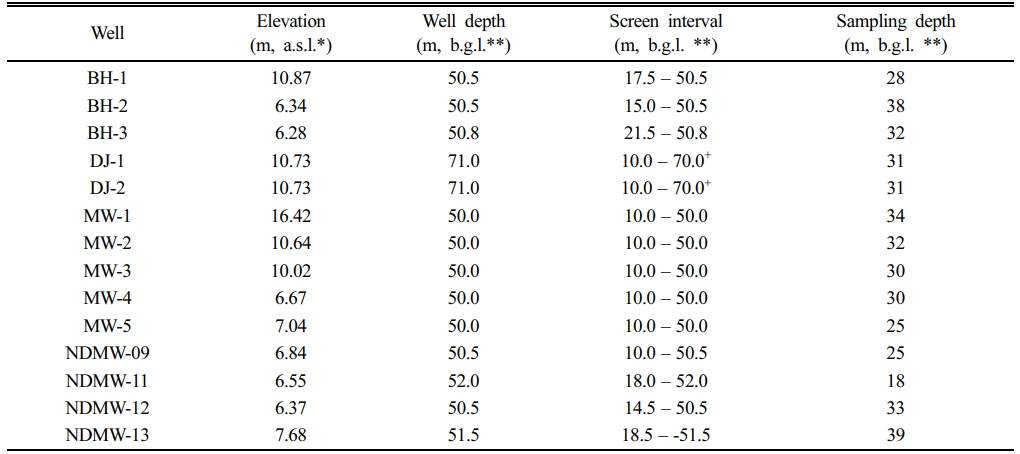

There are a total of fourteen groundwater monitoring wells (NDMW-09, NDMW-11–NDMW-13, MW-1–MW-5, BH-1–BH-3, DJ-1, DJ-2) within our study site. Detailed information on the monitoring wells is summarized in Table 1. The thickness of the unsaturated zone was relatively thin, based on the groundwater levels of the study site which ranged between 0.935 m (b.g.l.) and 1.420 m (b.g.l.) among the monitoring wells that were sampled on 4th April, 2022. Based on the elevation and groundwater level obtained, the local groundwater flow was determined to be in the direction of North-West to South-East as shown in Fig. 1(a).

Groundwater monitoring wells have a length ranging between 50 to 52 m, except for DJ-1 and DJ-2 which have a length of 71 m (Table 1). DJ-1 and DJ-2 wells are consisted of a casing of 20 m and the remainder of the well is an open borehole, while the other wells are all composed of a casing and screen. Fig. 1(b) shows the geological layers of the study site through the cross-sectional view between DJ, NDMW-09, and BH-2. The study site mainly consisted of 5 layers: landfill (silty sand), sedimentary layer (sand and silty clay), weathered soil (silty sand), weathered rock (mica schist) and bedrock (mica schist). Based on the well configuration and geological layers, all wells were observed to be bedrock wells.

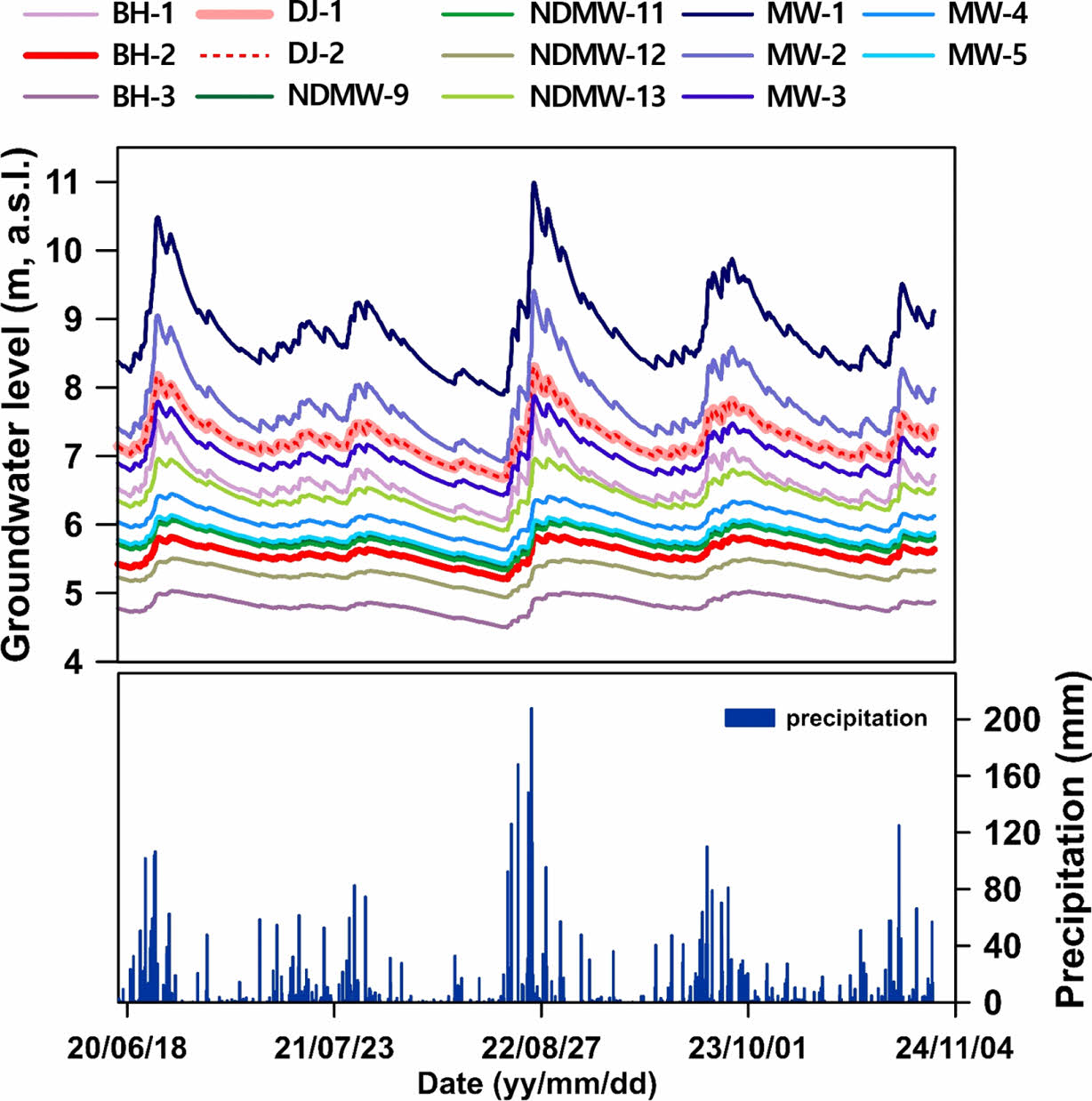

Daily precipitation was obtained from the nearest Automated Synoptic Observing System (ASOS) of Incheon station operated by the Korea Meteorological Administration (KMA) (KMA, 2024). Data was collected in from 1st January 2021 to 31st December 2022. The amount of precipitation was higher in between the months of July and August with a maximum value of 207.8 mm on 9th August, 2022 (Fig. 1(c)).

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Radon measurement

Radon concentrations in groundwater were measured using a RAD-7 radon-in-air monitor connected to a RAD-H2O accessory (Durridge Co., USA) in April and August 2022. A total of 11 groundwater samples were collected: DJ-1, BH-1, BH-2, BH-3, MW-1, MW-2, MW-3, MW-4, NDMW-11, NDMW-12, and NDMW-13. The samples were collected using polyethylene bottles and an MP-1 pump (Grundfos, USA). To facilitate the measurement, a bubbling kit was employed to degas radon from the water samples into the air in a closed loop. Each 250 ml water sample was connected in a closed circuit with a zinc sulfide-coated chamber for the detection of alpha activity. Radon was allowed to uniformly mix in the air by circulating in the closed circuit for a period of 5 to 10 minutes. The obtained radon concentrations were calibrated based on the short half-life of radon-222.

2.2.2. Two types of push-pull tests conducted in the study site

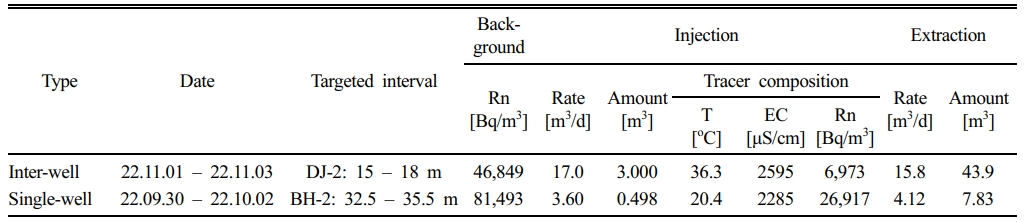

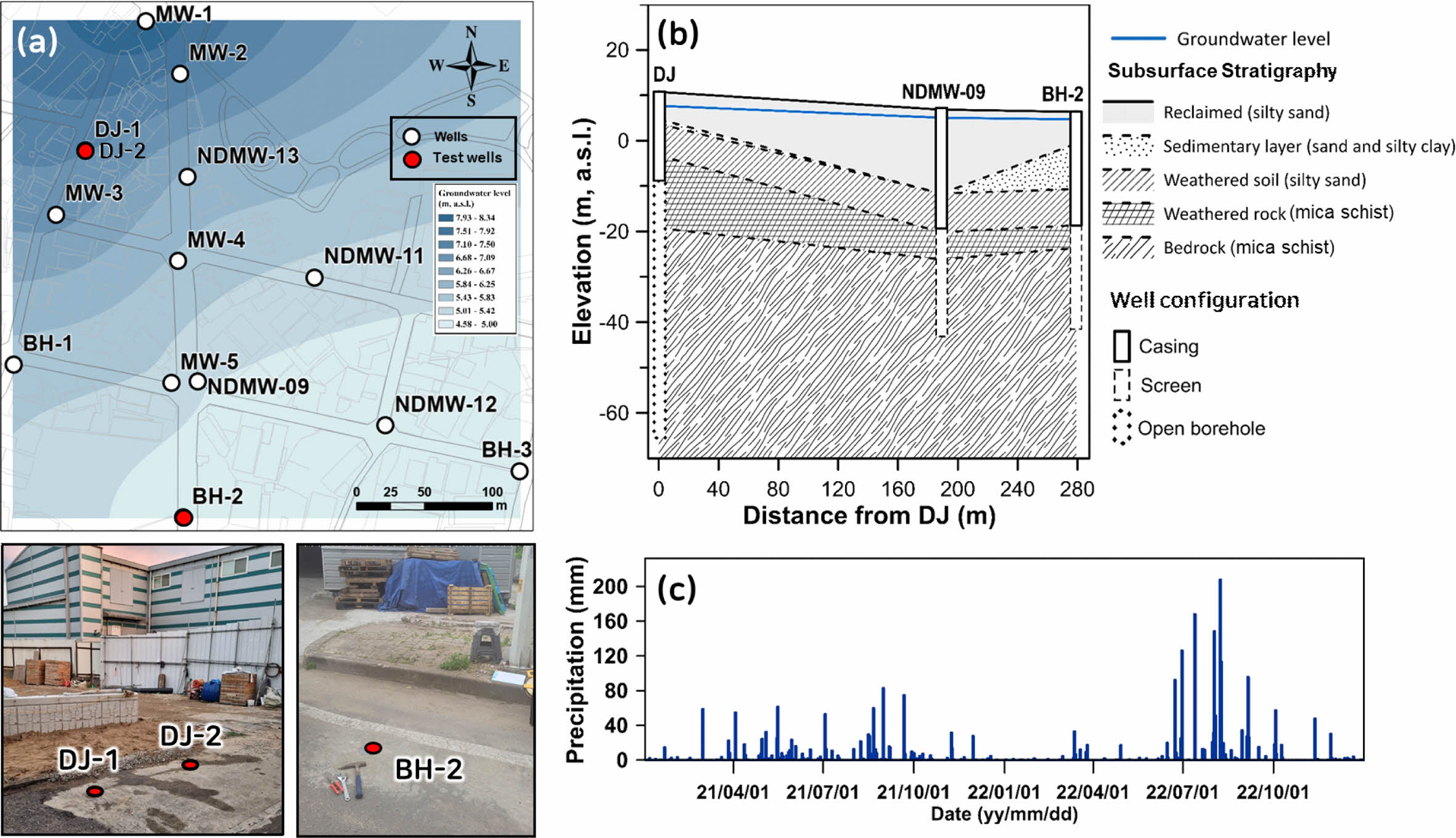

For this study, two types of push-pull tests were conducted as described in Fig. 2: ‘Case 1: Inter-Well Push-Pull Test’ and ‘Case 2: Single-Well Push-Pull Test’.

Case 1: Inter-Well Push-Pull Test: The inter-well push-pull test was conducted from 1st November 2022 to 4th November 2022 in wells DJ-1 and DJ-2. These two wells were selected based on previous sampling campaigns that showed relatively low DNAPL concentrations for these wells (Fig. 3). Consequently, providing an providing an experimental setting to figure out the behavior of radon without the consideration of partitioning to DNAPL. The target depth of the inter-well push-pull test was set between 15–18 m (b.g.l.) based on the presence of large-aperture fracture frequency, which was obtained through the borehole image processing results (see the left part of Fig. 2(a)). During the test, this target interval was isolated by a double packer system. Prior to starting the inter-well push-pull test, a forced gradient was generated by pumping the groundwater from DJ-1 at the same flow rate for the test (15.8 m3/d) to minimize disturbance of the flow field during the injection and extraction phases. Both conservative and non-conservative tracers were injected. Sodium chloride (NaCl) was dissolved to act as the conservative tracer. Tracer water consequently showed an electric conductivity (EC) of 2,595 μS/cm, which was higher than the background groundwater value (1,400 μS/cm). As the non-conservative tracer, radon was used. For the utilization of radon as a tracer, atmospheric air was artificially aerated to degas the radon of background groundwater (46,849 Bq/m3) down to 6,973 Bq/m3. Extracted water flowed through the flow cell to measure in-situ water quality parameters in a 30-second interval using a water quality meter (ProDss, YSI, USA). Water flowing out of the flow cell was sampled for the measurement of radon concentration. The radon concentration was measured using the RAD-7 radon-in-air monitor. The overall sampling sequence was elaborately constructed to prevent any possible influence of air bubbles on gas concentration. Detailed information on the experiments is in Table 2.

Case 2: Single-Well Push-Pull Test: The single-well push-pull test was conducted in well BH-2. The selection of the well was based on the previous sampling campaign results of the analysis of DNAPL concentrations for the 15 monitoring wells (see Section 3.1 for detailed information). Based on the results, well BH-2 showed the second highest concentration of TCE and the potential for it to be from a separate source other than the main source upgradient. Hence, the single-well push-pull tracer test, which had the purpose to verify and quantify the existence of liquid phase DNAPL within the swept area, was conducted at BH-2.

To determine the target depth interval, the vertical distribution of dissolved DNAPL concentrations within BH-2 were analyzed. Seventeen diffusion samplers were installed within the screen interval of the well from a depth of 16.5 to 48.5 m at a 2 m interval on 22nd July 2022. After the recommended time of installment, the diffusion samplers were recovered and analyzed by Sanji University using the GC/MS (Saturn 2100T, VARIAN) for the dissolved TCE concentration analysis. As a result, the interval between 32.5 to 48.5 m (b.g.l.) showed relatively elevated TCE concentration values compared to the shallower depths (see left part of Fig. 2(b)). Based on these results, the targeted interval was selected to be between 32.5 and 35.5 m (b.g.l.). Inflatable double packers were used to isolate this interval, which enabled the injection and extraction of the tracer water for this specific depth.

Tracer water consisted of a conservative and a non-conservative tracer. For the conservative tracer and non-conservative tracer uranine and radon were used respectively. Radon has the property of phase partitioning to the liquid phase NAPL which has been commonly utilized to quantify the liquid phase NAPL (Davis et al., 2002; Schubert et al., 2007; Semprini et al., 2000). Groundwater for the tracer water was pumped from BH-2 at a depth of 40 m. The pumped water was put into a 1-ton tank. Thereafter, to degas the water of radon, artificial aeration by bubbling atmospheric air into the tank (for 8.3 hr) and natural aeration by leaving the tank open to the air (for 14 hr) were proceeded. Finally, uranine was dissolved into the water. The manufactured tracer water consisted of 367.1 ppm uranine and 26917.2 Bq/m3 radon. For the analyzation of the background concentration of the tracers, groundwater sampling was conducted for the targeted interval a day before the tracer water injection. Uranine and radon concentrations were 0 ppm and 81,493 Bq/m3 respectively.

The single-well push-pull test was conducted from 30th September 2022 to 2nd October 2022. The test setup was as shown in the right side of Fig. 2(b). The experimental section within the well was isolated between a 32.5–35.5 m (b.g.l.) using a double packer system. Between the two packers, tracer injection extraction was conducted. 0.498 m3 of tracer water was injected at an average rate of 3.6 m3/d, which was followed up by 7.83 m3 of groundwater extraction at an average rate of 4.12 m3/d. Extraction was persisted until the recovery rate of uranine was more than 90%. During the extraction period sampling of uranine and radon were conducted 20 times.

2.2.3. Analytical solution

Gelhar and Collins (1971) derived the approximate solution for the relative tracer concentration during the extraction phase of the tracer test. This is based on the governing equation of solute transport affected by advection, dispersion and sorption within a radial transport flow system of a homogeneous confined aquifer:

where C and S are dissolved and sorbed phase concentrations respectively [ML-3], n is bulk density [ML-3], n is effective porosity [-], t is time [T], aL is longitudinal dispersivity [L], v is average pore water velocity [LT-1], r is radial distance [L]. The linear equilibrium sorption isotherm model is applied. Once the tracer water is injected, the maximum value of the frontal point is defined as r̂max [L]:

where Vinj is total volume of tracer water injected [L3], R is retardation factor [-], and rw is the injection/extraction well radius [L]. Based on these values, the normalized tracer concentration (C*) [-] can be derived as the following:

|

Fig. 1 (a) Groundwater levels within the study site, with black circles representing monitoring wells and red filled circles indicating locations where tracer tests were conducted (DJ-1, DJ-2, and BH-2). (b) Cross-sectional view of the study site. (c) Daily precipitation recorded at a nearby monitoring station from 1st January 2021, to 31th December 2022. |

|

Fig. 2 Schematic diagram of the experimental setup and rationale for the sections where experiments were conducted: (a) Inter-well push-pull test, (b) Single-well push-pull test. |

|

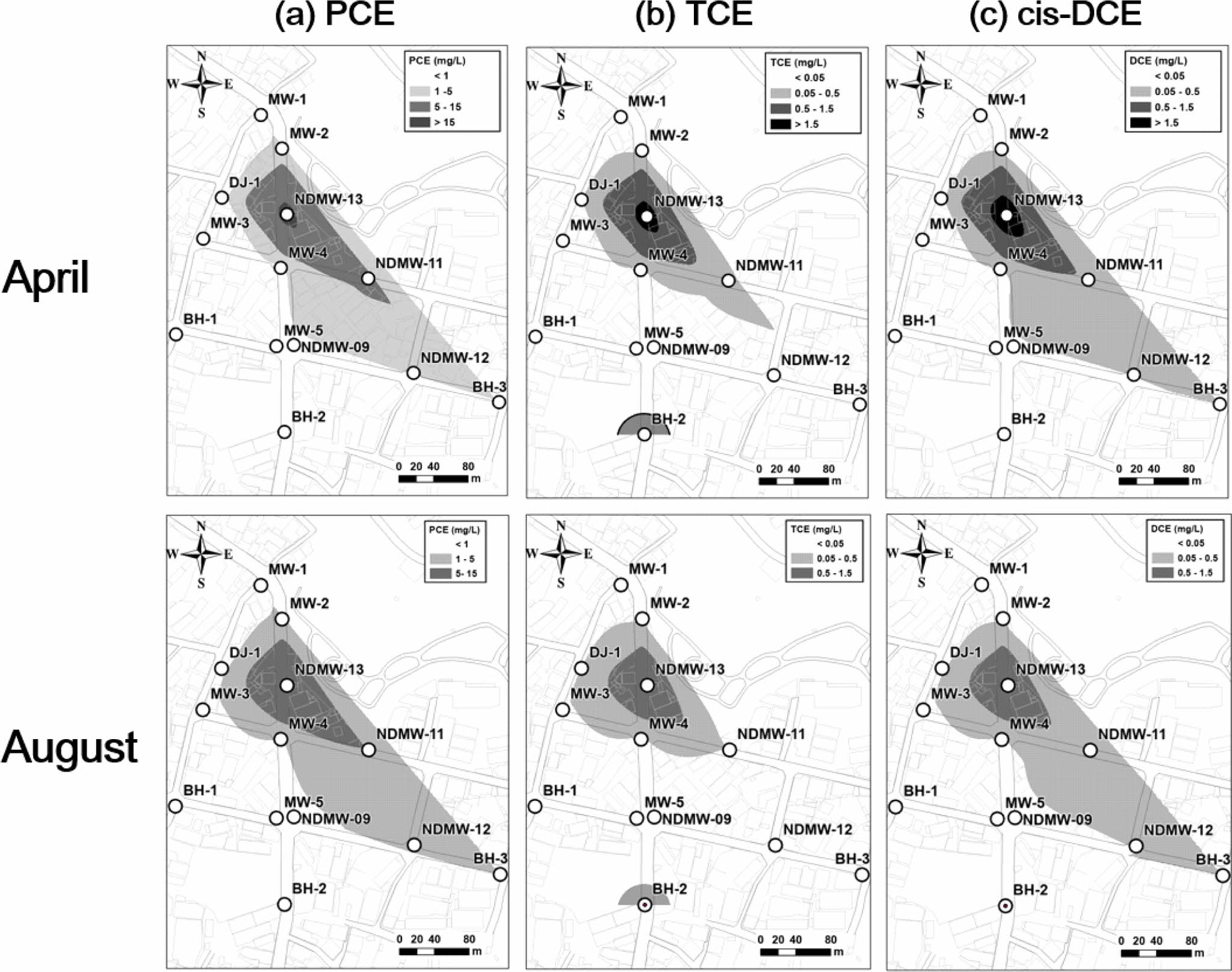

Fig. 3 Distribution of dissolved DNAPL concentrations in groundwater across two seasons (April and August): (a) PCE, (b) TCE, and (c) cis-DCE. |

|

Table 1 Information for monitoring groundwater wells installed at the study site |

*is the a.s.l. = above sea level and **is the b.g.l = below ground level. |

3.1. Spatio-temporal distribution of DNAPL conta- minants and radon

At the study site, the dissolved concentrations of chlorinated ethenes—PCE, TCE, 1,2 cis-DCE, and VC—were monitored during two seasons, April and August 2022 (Fig. 3). The results showed that the sum of PCE, TCE, cis-DCE, and VC decreased slightly in all monitoring wells in August, the wet season. In April, the dry season, the average concentrations of PCE, TCE, 1,2 cis-DCE, and VC were 2.662, 0.318, 0.265, and 0.011 mg/L, respectively, resulting in a total average of 3.255 mg/L. In August, the wet season, the average concentrations of PCE, TCE, and 1,2 cis-DCE were 2.298, 0.159, and 0.159 mg/L, respectively, totaling 2.621 mg/L. In both seasons, high total values were observed for NDMW-11 and NDMW-13, whereas low values were noted for MW-1, MW-3, and BH-1. The sum of contaminant concentrations decreased for BH-2, MW-2, NDMW-11, and NDMW-13 in the wet season. Generally, the source zone exhibited decreasing patterns during the wet season.

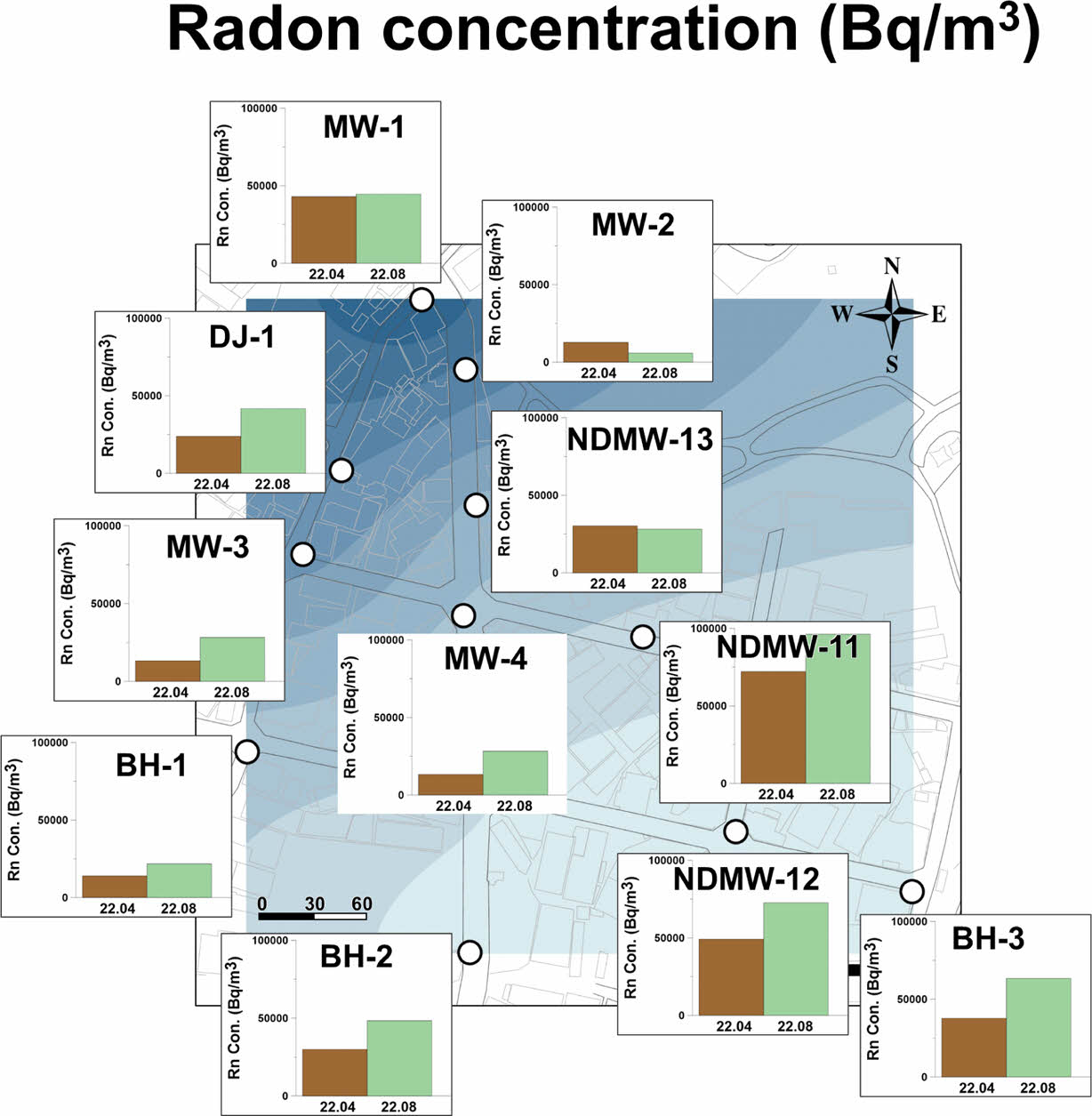

The spatio-temporal distribution of radon was also analyzed during the two seasons (Fig. 4). The average radon concentration was 31,568 Bq/m³ in April (dry) and 44,077 Bq/m³ in August (wet), which aligns with the general phenomenon of increased values in the wet season. High values (> 50,000 Bq/m³) were observed in NDMW-11 during the dry season and at BH-3, NDMW-11, and NDMW-12 during the wet season. According to the principle of radon deficiency, radon concentrations generally decrease as the sum of contaminant concentrations increases. This phenomenon was only observed in BH-2 and NDMW-11. However, most groundwater wells did not follow this principle, indicating that other factors, such as seasonal effects, are predominant at this study site. An increase in radon concentration was observed in most groundwater wells, except MW-2 and NDMW-13. This pattern could be attributed to the mixing effect from local precipitation, consistent with the contaminant results (Kim et al., 2024). Groundwater flow was directed from MW-2, located on a hill, to NDMW-13. Groundwater level modeling data also supported this (Fig. 5). Additional modeling data was illustrated in Supplementary file with Fig. S1-S3. Wells MW-1 and MW-2 responded significantly to precipitation, with a notable increase (> 20,000 Bq/m³) observed at BH-3, NDMW-11, and NDMW-12, which showed a delayed response to water level changes compared to the other wells. In other words, if the contaminated zone is located in a bedrock aquifer, the phase partitioning of radon to TCE may not the dominant process affecting radon concentration patterns. Therefore, to evaluate the application of radon as a tracer for detecting DNAPLs, two pumping tests were conducted: (1) an inter-well push-pull test in the non-DNAPL contaminated zone (case 1) and (2) a single-well push-pull test in the DNAPL contaminated zone (case 2).

3.2. Push-pull test to evaluate the application of radon for DNAPL tracing

3.2.1. Case 1: Inter-well push-pull test without DNAPL contamination

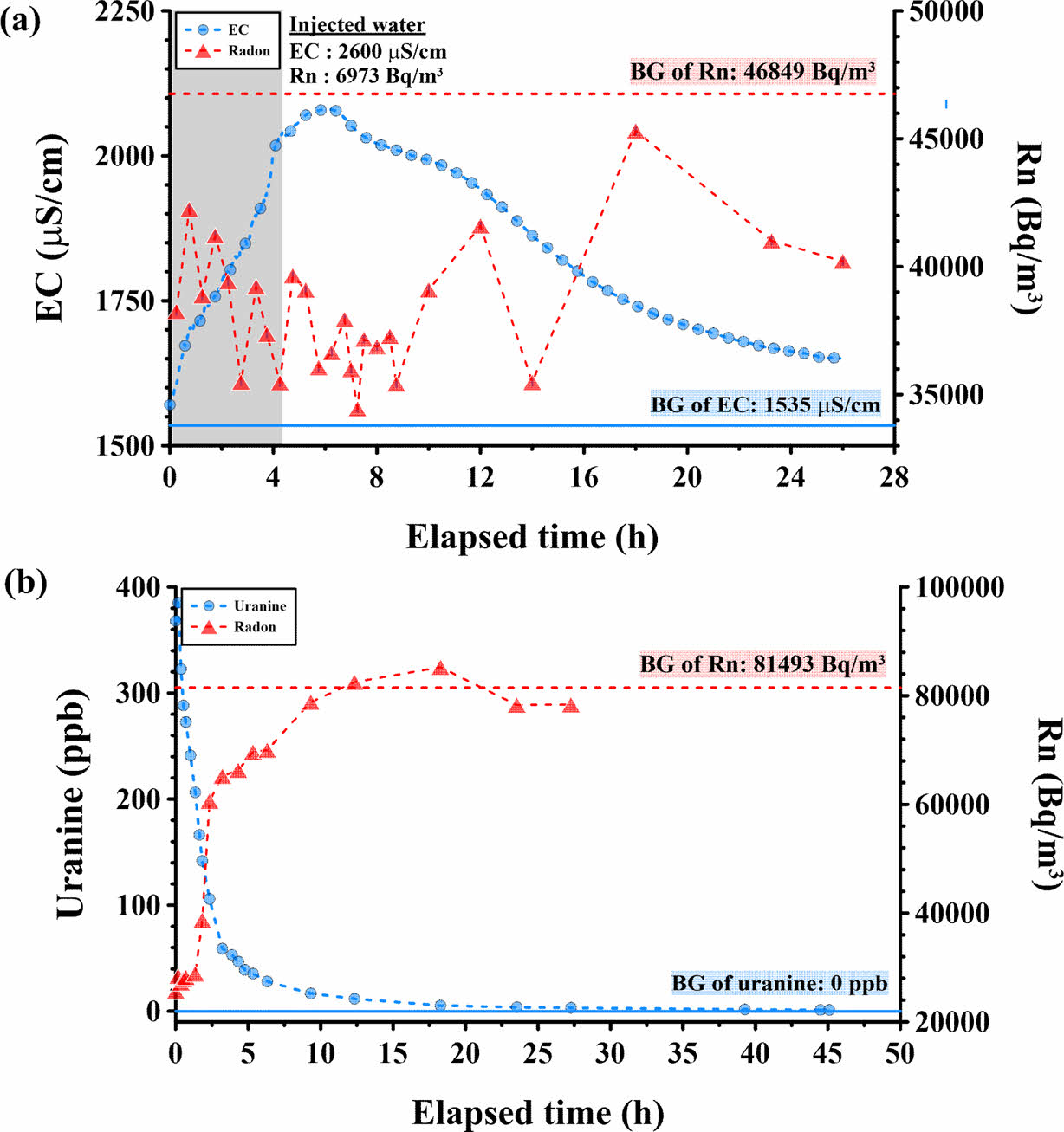

The BTCs of EC and radon during extraction are shown in Fig. 7. During the push-pull test, 80% of conservative tracer was recovered. For radon concentration, similar to the above single-well push-pull test, the background concentration was much higher than that of injected water so a decrease in radon concentration was observed. Around 7.5 hours after the start of injection, radon concentration showed the lowest value as a peak. Similar to radon, EC also started to decrease after 7.5 hours. Unlike the single-well push-pull test under the contaminated site, the inter-well push-pull test without contamination showed a similar peak time between EC and radon concentration (Fig. 5(a)). Here, one interesting point is that the EC value showed the maintenance of peak for about an hour (from 6.1 to 7.5 hours) before it decreased during extraction. As the finite pulse type of peak showed, injected sodium chloride was transported from DJ1 well to DJ2 well for 1.5 m in Euclidean distance and recovered well up to 80% during 26 hours of extraction. Also, the resulted radon concentration from the inter-well push-pull test showed the influence of mixing due to the wellbore or fractures as a vibration of concentration values. This indicated that without contamination of DNAPL, the radon tracer may act similar to the conservative tracer, dominantly affected by mixing along with groundwater flow dynamics as also founded in Hoehn et al. (1992), and Bertin and Broug (1994).

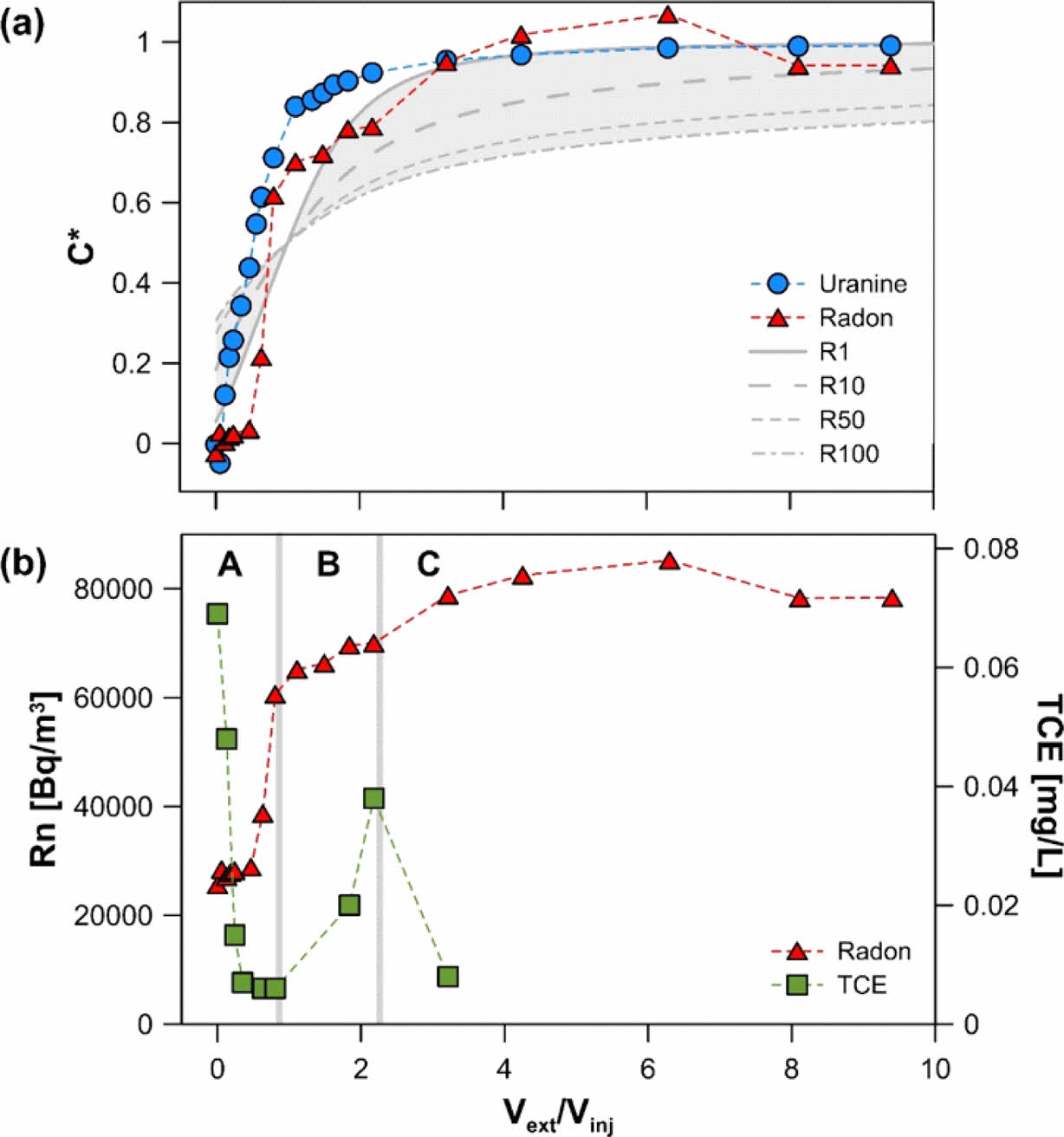

3.2.2. Case 2: Single-well push-pull test in DNAPL contaminated zone

The extraction BTC of uranine and radon are shown in Fig. 5(a). For the comparison between the two tracers, normalized concentrations (C*) were used as shown in Fig. 7(a). For uranine C* = 1- C/C0, and in the case for radon, since the tracer water was aerated for the radon concentration to be lower than the background, C* = (C-C0)/(Cbg/C0). C is the measured concentration, C0 is the concentration within the tracer water before injection, and Cbg is the background concentration. The uranine BTC showed a gradual increase with no evident change in curvature. This indicated the validity of the assumption of a Fickian dispersion behavior during the extraction phase (Gouze et al., 2008). In other words, the application of Eq. (3) which assumed radial flow in a homogeneous confined aquifer can be considered valid. Despite the fact that the targeted interval of the single-well push-pull test was within the bedrock aquifer, the development of a dense fractured network allowed the assumption of an equilibrated porous media.

The porosity and dispersivity in well BH-2 were determined using Eq. (3) by finding the best fit curve with the uranine BTC, due to the absence of field hydraulic tests at this well. Since uranine was used as a conservative tracer, R was set as 1 indicating no retardation. As a result, the derived values were 0.015 for porosity and 0.275 m for dispersivity, which showed an RMSE of 0.132 with the normalized uranine concentrations.

Based on these derived hydraulic parameters, the retardation factor (R) was varied to determine the degree of retardation of radon to liquid TCE within the swept area (Fig. 7(a)). However, the radon BTC did not show an appropriate match since the curvature varied. Since the aquifer was earlier verified of being assumed an equilibrated porous media, this non-fickian behavior of radon did not indicate the probability of varying aquifer characteristics, but rather the non-homogeneous distribution of free phase TCE. When deriving this equation, the ideal transport conditions including the spatially uniform linear equilibrium sorption was assumed (Gouze et al., 2008; Schroth et al., 2000). In other words, the existence of a constant amount of free-phase DNAPL within the swept area during the push-pull test was assumed. However, heterogeneous contaminant distribution due to the presence of contaminant pools can limit the application of the solution (Davis et al., 2002; Willson et al., 2000). For this reason, this could also lead to the poor fit to the extraction phase BTC (Schroth et al., 2000). The field results of this study also showed aligning results, so it was determined that there was a possibility for heterogeneous TCE distribution around BH-2.

Instead of determining a specific retardation factor, the radon BTC was compared with the dissolved TCE BTC and was analyzed of three distinctive sections (section A – C) (Fig. 7(b)). Within each section, radon and TCE concentrations showed characteristic trends. Radon concentrations varied between 25,588 Bq/m3 and 85,262 Bq/m3, and TCE concentrations varied between 0.006 mg/L and 0.069 mg/L. The background and injection water concentration for radon was 81,493 Bq/m3 and 26,917 Bq/m3 respectively. The background concentration of TCE was 0.005 mg/L. For section A, the radon concentrations rapidly increased, while dissolved TCE concentrations rapidly decreased. Two potential reasons for the change in radon concentrations are mixing of injected tracer water and background water, or phase partitioning of radon to liquid TCE. In order to determine the possibility of the influence of phase partitioning, the derivative {{{EQUATIONS}}} of the curves for varying retardation factors from 1 to 100 were compared with the slope of rapid increase. The maximum possible derivative value of the theoretical curves was 0.48, whereas the slope of rapid increase for the field samples was 2.33. This shows that this drastic change cannot be solely explained by the phase partitioning of radon to TCE. It was more likely to be influenced by the mixing procedure between the injected tracer water and background water, since the TCE concentration trend also indicated this process. As for section B, the radon concentration trend changed to a mild increase, and the TCE concentrations started to suddenly increase. In this case, this section was likely to be influenced by the phase partitioning of radon to TCE. If this section were to be explainable by mixing, the trend of radon concentration change would be a continuum of section A. However, the evident change of trend in radon backed up the possibility for the influence of nearby free phase TCE. In addition to the radon change, the TCE change also gave evidence to this interpretation. Within this section, TCE concentration increased from 0 to 0.04 mg/L. This increase can be considered to be a meaningful difference since it is a value higher than all fourteen wells within the study area except three (Fig. 3). Last off, section C has a relatively more rapid increase of radon concentration than the previous section and TCE concentrations decreased. The radon concentrations reached the background concentration and TCE concentration changed back into the background concentration. Also, the recovery rate of uranine at this point was approximately 80% already. Therefore, this indicated that the mixing process with the background could be predicted to be dominant.

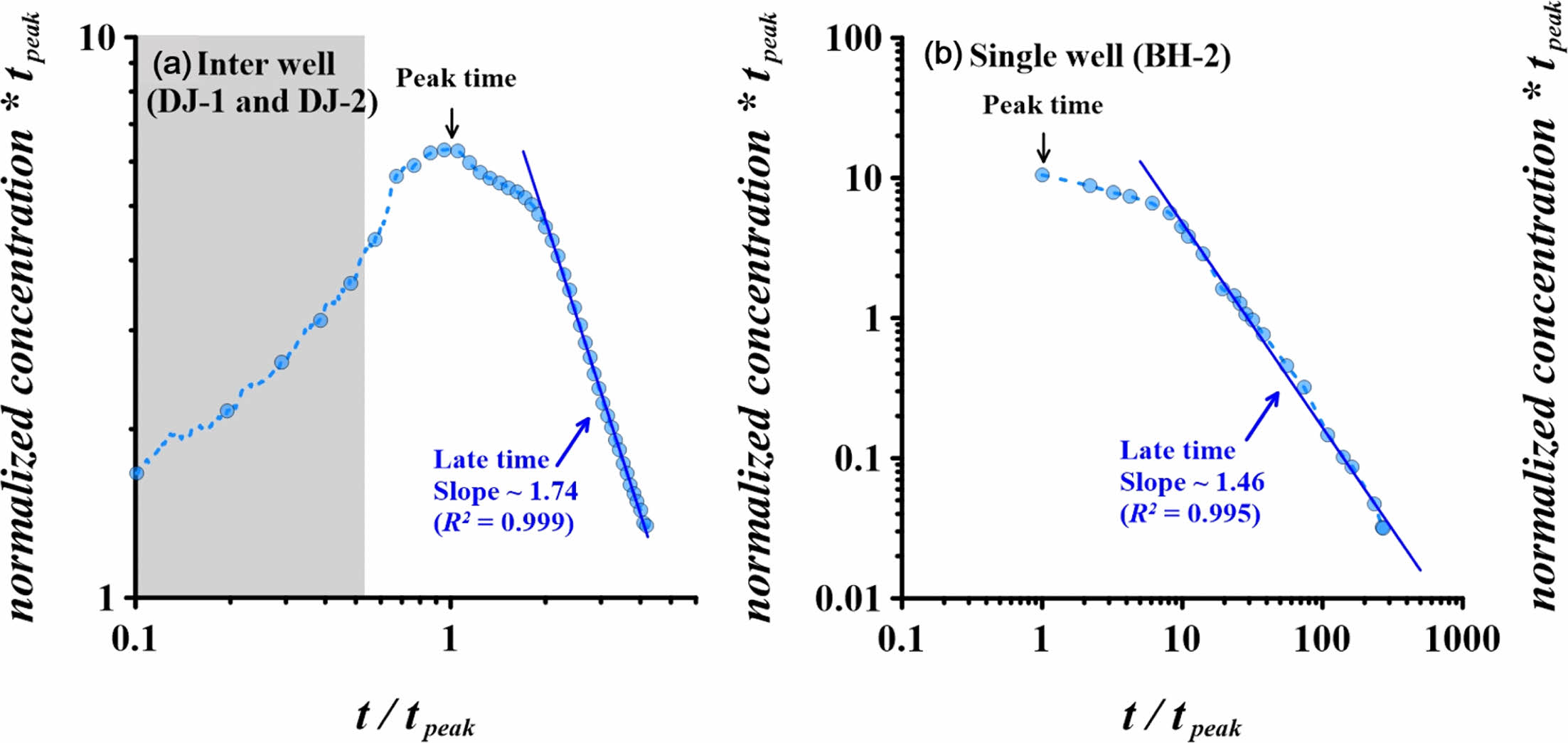

3.2.3. Comparison of flow characteristics between single and inter-well push-pull tests

To compare the behavior between conservative tracers of case 1 (NaCl) and case 2 (uranine), the scaling factor of the power law of each BTC was obtained by calculating the normalized time (time divided by the peak time) and normalized concentration multiplied by the peak time to ensure the area under the BTC equals 1 (Kang et al., 2015) (Fig. 8). The resulted power-law late-time scaling was ~1.74 for case 1 (DJ wells) and ~1.46 for case 2 (BH-2). This slope can indicate the degree of heterogeneity (Kang et al., 2015), which means that various flow velocities and preferential paths could affect the BTC (Bianchi et al., 2011). Generally, single-well push-pull tests show to be less sensitive to heterogeneity compared to convergent tests (Tsang, 1995; Hansen et al., 2016). However, in this study, the single-well push-pull test (case 1) showed a gentler slope of ~1.46 which suggested the possibility of relatively larger influence of heterogeneity. There could be two possible reasons. First, BH-2 shows slower velocity than the DJ wells (Table S1). The artificial injection and extraction procedure could lead to larger variation in flow velocities in cases where slower background groundwater velocity was present (Kang et al., 2015) resulting the gentle slope of late-time scaling. Second of all, the geological characteristics of the targeted interval for the two tests differ. While the targeted depth of BH-2 was located across the bedrock layer, the targeted depth of DJ wells was located across the weathered rock layer which has a higher possibility to show less heterogeneous properties. Hence, both spatial and vertical characteristics could influence the complexity of the groundwater system leading to the varying heterogeneity of conservative tracers’ behavior during the push-pull experiments. Furthermore, this also has the potential to influence the non-conservative tracer behavior. As mentioned before, when we examined the single-well push-pull BTC of radon, we observed a tendency that did not align with the curve described by the traditional analytical solution. with the curve described by the traditional analytical solution. In section 3.2.2., we had mentioned that this could be due to the heterogeneity of the TCE saturation within the area of influence of the single-well push-pull test (Davis et al., 2002; Willson et al., 2000). Another possible explanation for this phenomenon of the non-conservative tracer can be related to the characteristic that the conservative tracer was analyzed to have. It was explained that the heterogeneity in the flow field may resulted in the violation of the assumption of radial flow (Kang et al., 2014) which explains the non-alignment of the radon BTC curve with the traditional analytical solution that is based on the assumption of radial flow (Davis et al., 2002).

3.3. Verification of radon tracer and limitations

In cases where groundwater wells are located in a bedrock aquifer, the application of the radon tracer possess numerous constraints to quantify DNAPL since phase partitioning may not be the dominant process affecting radon concentrations. Although seasonal effects, such as mixing due to local precipitation, were generally observed at the study site, the behavior of each groundwater well could not be interpreted using the principle of radon deficiency solely.

To evaluate radon as a reliable tracer for DNAPL characterization, two push-pull tests were conducted. First, the inter-well push-pull test demonstrated that the predominant physical processes affecting radon concentrations were mixing processes with other water bodies. In contrast, the single-well push-pull test provided insights into the dominant physical process at each zone of influence by evaluating three separate sections. Section B was found to be influenced by the phase partitioning of radon to TCE, indicating the presence of free phase TCE between radial distances of 1.98 m and 2.77 m. Outside of this area, free phase TCE was not present in sufficient quantities to significantly affect the radon and TCE BTCs, making mixing processes between the injected tracer and background water dominant. Consequently, this sectional analysis and the comparison of radon and TCE BTCs allowed for the identification of entrapped TCE zones.

The concept of DNAPL deficit has primarily been applied to porous media, but its application in fractured rock aquifers has been limited. In the case of this study site, applying this concept to the section corresponding to the fractured rock aquifer revealed some inconsistencies during the interpretation of experimental results. To address this, this study first examined the behavior of radon in uncontaminated areas, and then conducted experiments in contaminated areas. This demonstrated that the distribution of DNAPL using radon as a tracer could also be applied within the fracture zones. Thus, the results indicate that radon in groundwater can be applied as a reliable tracer to investigate DNAPLs migration alongside groundwater flow in a bedrock aquifer. However, considering the half-life of radon, the experiments are recommended to be conducted within a timeframe of approximately 3–4 days. Given that most push-pull tests are relatively short duration experiments, this approach is expected to be well-suited for site-specific applications.

|

Fig. 4 Radon concentrations in groundwater for the two seasons: brown color represents April (dry season) and green color represents August (wet season) |

|

Fig. 5 Breakthrough curves (BTCs) of tracers for each experiment: (a) Breakthrough curve of EC and Rn during inter well push pull experiment. The gray shade indicates the injection period (4.2 h). Blue circles are the measured EC and red triangles are the measured concentration of radon. Blue straight line means the background of EC and red dot line means the radon of background groundwater. (b) Breakthrough curve of uranine and Rn during single-well push-pull experiment. Blue circles are the measured uranine and red triangles are the measured radon concentrations. The blue solid line and red dotted line indicate the background groundwater concentration of uranine and radon respectively. |

|

Fig. 6 Modeled groundwater level monitoring data from 14 wells at the study site, spanning from June 20, 2018, to November 4, 2024. The figure below indicates precipitation data during this period. |

|

Fig. 7 Single-well push pull test results: (a) Normalized uranine and radon concentrations (C* ) depending on the relative volume of extraction to injection (Vext/V). Blue circles indicate the sampled uranine values, and red triangles indicate the sampled radon values. Grey lines depict the theoretical relationship between Vext/V and C* . R1 is the best fit curve for the uranine data points (n = 0.015, αL= 0.4). The dotted lines each correspond to the curves with retardation factors (R) of 1, 10, 50, and 100. The grey shaded area is the explainable area by the Eq. (3) with varying R values. (b) Radon and TCE concentrations depending on the relative volume of extraction to injection (Vext/V). Red triangles indicate the radon values, and green squares indicate the dissolved TCE values. |

|

Fig. 8 Breakthrough curve (BTC) for normalized concentration to normalized time to determine the slope of BTC: (a) Inter-well (DJ-1 and DJ-2), (b) Single-well (BH-2). |

While radon has been used as a promising tool for DNAPLs tracing in groundwater, its effectiveness can be constrained by environmental factors, geological conditions, and mixing processes. In particular, within a bedrock aquifer zone, DNAPLs can be influenced by various factors through highly permeable fractures. This study aimed to conduct push-pull tests in a bedrock aquifer to verify the application of radon as a reliable natural tracer for DNAPLs in groundwater.

Firstly, an inter-well push-pull test was performed in an area absent of DNAPL contamination, revealing that radon concentrations were predominantly affected by mixing effects, with a recovery rate of the conservative tracer of approximately 80%. Secondly, a single-well push-pull test was conducted in the DNAPLs-contaminated zone. This test demonstrated that radon concentrations were initially influenced by phase partitioning effect with TCE within a certain radial range and later dominated by mixing processes with other water bodies, such as rainfall. The comparison of radon's transport characteristics as a tracer in these two experiments offered valuable insights into using radon to assess the radial ranger of DNAPL distribution within a bedrock aquifer. Overall, this study highlights the potential of using radon concentrations in groundwater as a useful tracer for monitoring DNAPL characteristics in a bedrock groundwater system. In wet season, the DNAPL distribution should be investigated in consideration of the partitioning effects and the seasonal mixing effects. The findings provide valuable insights for future research on groundwater contamination and remediation strategies.

This work was supported by Korea Environment Industry & Technology Institute(KEITI) through “Activation of remediation technologies by application of multiple tracing techniques for remediation of groundwater in fractured rocks” funded by Korea Ministry of Environment (MOE)(Grant number:20210024800002/1485017890).

The data that supports the findings of this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

This manuscript was not influenced by any competing financial interests or personal relationships. It does not also have the potential competing interests.

- 1. Barrio-Parra, F., Izquierdo-Díaz, M., Díaz-Curiel, J., and De Miguel, E. (2021). Field performance of the radon-deficit technique to detect and delineate a complex DNAPL accumulation in a multi-layer soil profile. Environmental Pollution, 269, 116200.

-

- 2. Berkowitz, B. (2002). Characterizing flow and transport in fractured geological media: A review. Advances in Water Resources, 25(8-12), 861-884.

-

- 3. Bertin, C., and Bourg, A. C. (1994). Radon-222 and chloride as natural tracers of the infiltration of river water into an alluvial aquifer in which there is significant river/groundwater mixing. Environmental Science & Technology, 28(5), 794-798.

-

- 4. Bianchi, M., Zheng, C., Tick, G. R., and Gorelick, S. M. (2011). Investigation of small‐scale preferential flow with a forced‐gradient tracer test. Groundwater, 49(4), 503-514.

-

- 5. Briganti, A., Voltaggio, M., Carusi, C., and Rainaldi, E. (2024). Radon deficit technique applied to the study of the ageing of a spilled LNAPL in a shallow aquifer. Journal of Contaminant Hydrology, 263, 104342.

-

- 6. Brusseau, M. L., Nelson, N., and Cain, R. B. (1999). The partitioning tracer method for in-situ detection and quantification of immiscible liquids in the subsurface. In: ACS Publications.

-

- 7. Davis, B., Istok, J., and Semprini, L. (2002). Push–pull partitioning tracer tests using radon-222 to quantify non-aqueous phase liquid contamination. Journal of Contaminant Hydrology, 58(1-2), 129-146.

-

- 8. Davis, B., Istok, J., and Semprini, L. (2003). Static and push‐pull methods using radon‐222 to characterize dense nonaqueous phase liquid saturations. Groundwater, 41(4), 470-481.

-

- 9. Davis, B., Istok, J., and Semprini, L. (2005). Numerical simulations of radon as an in situ partitioning tracer for quantifying NAPL contamination using push–pull tests. Journal of Contaminant Hydrology, 78(1-2), 87-103.

-

- 10. Engelmann, C., Lari, K. S., Schmidt, L., Werth, C. J., and Walther, M. (2021). Towards predicting DNAPL source zone formation to improve plume assessment: Using robust laboratory and numerical experiments to evaluate the relevance of retention curve characteristics. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 407, 124741.

-

- 11. Gelhar, L., and Collins, M. (1971). General analysis of longitudinal dispersion in nonuniform flow. Water Resources Research, 7(6), 1511-1521.

-

- 12. Gouze, P., Le Borgne, T., Leprovost, R., Lods, G., Poidras, T., and Pezard, P. (2008). Non‐Fickian dispersion in porous media: 1. Multiscale measurements using single‐well injection withdrawal tracer tests. Water Resources Research, 44(6).

-

- 13. Hoehn, E., Von Gunten, H. R., Stauffer, F., and Dracos, T. (1992). Radon-222 as a groundwater tracer. A laboratory study. Environmental Science & Technology, 26(4), 734-738.

-

- 14. Istok, J., Field, J., Schroth, M., Sawyer, T., and Humphrey, M. (1999). Laboratory and field investigation of surfactant sorption using single‐well,¡°push‐pull¡± tests. Groundwater, 37(4), 589-598.

-

- 15. Istok, J. D. (2012). Push-pull tests for site characterization (Vol. 144): Springer Science & Business Media.

- 16. Jin, A., Wang, Q., and Zhan, H. (2024). A novel four phase slug single-well push–pull test with regional flux: forward modeling and parameter estimation. Journal of Hydrology, 630, 130705.

-

- 17. Kang, P. K., Le Borgne, T., Dentz, M., Bour, O., and Juanes, R. (2015). Impact of velocity correlation and distribution on transport in fractured media: Field evidence and theoretical model. Water Resources Research, 51(2), 940-959.

-

- 18. Kim, J., Kaown, D., and Lee, K.-K. (2024). Coupling of radon and microbial analysis for dense non-aqueous-phase liquid tracing and health risk assessment in groundwater under seasonal variations. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 134939.

-

- 19. Lerner, D., Kueper, B., Wealthall, G., Smith, J., and Leharne, S. (2003). An illustrated handbook of DNAPL transport and fate in the subsurface.

- 20. Mattia, M., Tuccimei, P., Ciotoli, G., Soligo, M., Carusi, C., Rainaldi, E., and Voltaggio, M. (2023). Combining radon deficit, NAPL concentration, and groundwater table dynamics to assess soil and groundwater contamination by NAPLs and related attenuation processes. Applied Sciences, 13(23), 12813.

-

- 21. Schroth, M., Istok, J., and Haggerty, R. (2000). In situ evaluation of solute retardation using single-well push–pull tests. Advances in Water Resources, 24(1), 105-117.

-

- 22. Schubert, M., Paschke, A., Lau, S., Geyer, W., and Knöller, K. (2007). Radon as a naturally occurring tracer for the assessment of residual NAPL contamination of aquifers. Environmental Pollution, 145(3), 920-927.

-

- 23. Semprini, L., Hopkins, O. S., and Tasker, B. R. (2000). Laboratory, field and modeling studies of radon‐222 as a natural tracer for monitoring NAPL contamination. Transport in Porous Media, 38, 223-240.

-

- 24. Willson, C. S., Pau, O., Pedit, J. A., and Miller, C. T. (2000). Mass transfer rate limitation effects on partitioning tracer tests. Journal of Contaminant Hydrology, 45(1-2), 79-97.

-

This Article

This Article

-

2024; 29(6): 141-153

Published on Dec 31, 2024

- 10.7857/JSGE.2024.29.6.141

- Received on Oct 23, 2024

- Revised on Nov 29, 2024

- Accepted on Dec 19, 2024

Services

Services

- Abstract

1. introduction

2. materials and methods

3. results and discussions

4. conclusion

- Acknowledgements

- Data Availability Statement

- Conflicts of Interest

- References

- Full Text PDF

Shared

Correspondence to

Correspondence to

- Kang-Kun Lee

-

School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Seoul National University, Seoul 08826, Republic of Korea

- E-mail: kklee@snu.ac.kr