- Assessment of Children’s Exposure Risk to Potentially Hazardous Elements in Playground Soil in South Korea

Lee Hyunkyung*, Kim Gyunhee, Kim Chanhyuk, Kim Jisoo, Jeong Yunha, and Lim Juhee

Gyeonggi Province Institute of Health and Environment, Gyeonggi Province 16381, Korea

- 어린이 놀이터 토양의 잠재적 유해요소에 대한 오염도 및 노출 위험 평가

이현경*ㆍ김균희ㆍ김찬혁ㆍ김지수ㆍ정윤하ㆍ임주희

경기도보건환경연구원

This article is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This study evaluated the environmental safety of playground soil in children’s activity spaces located in five cities of Gyeonggi Province, where child population density is high. All 50 study sites met the environmental safety standards for heavy metals and parasitic eggs (ova) set by the Environmental Health Act. Fecal coliform contamination was detected in the playground soil, with 23 sites (46%) testing positive by membrane filtration and 36 sites (72%) testing positive by enzyme substrate method. The levels of heavy metals in the playground soil were below the soil contamination concern standards (Category 1) at all sites, but the concentrations of cadmium (Cd) and arsenic (As) were higher than those found in background areas of Gyeonggi Province. The average in vitro bioaccessibility for oral exposure was 23%, with copper (Cu) and lead (Pb) showing bioaccessibility greater than 46%, indicating a potential risk of children’s exposure to heavy metals through the soil. The bioaccessibility from skin contact was significantly lower, at 0.3%. Although the playground soil met legal standards, the potential risks from heavy metals and biological contamination remain. Therefore, continuous monitoring of heavy metals and fecal coliform contamination, along with further research, is necessary to ensure the safety of playground soil. This will provide essential data to secure the safety of playground surfaces and support the creation of environments where children can play in a healthy and safe setting.

Keywords: children’s playground, parasite, fecal coliform, heavy metal, in vitro bioaccessibility

Children’s activity spaces refer to areas primarily used by children under the age of 13, such as playgrounds, daycare centers, kindergartens, and elementary schools. These spaces are required to comply with the environmental safety standards set forth by the Environmental Health Act (Ministry of Environment, 2021). In urban parks and residential complexes, children often view playground soil as a form of play material. As a result, they frequently touch the soil with their hands and engage in hand-to-mouth behavior, uninten- tionally ingesting the soil (National Institute of Environmental Research, 2007).

A study by Jang et al. (2014) found that the average daily soil ingestion among children in South Korea, including Gyeonggi Province, is 118.3 mg/day. In the top 10% of children, the daily ingestion rises to 286.2 mg/day, and in the top 5%, it reaches 898 mg/day. This exceeds the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) recommended exposure factor of 100 mg/day by 18% (US Environmental Protection Agency, 1997).

Children’s higher metabolic rates—1.5 times that of adults —result in a greater absorption rate of heavy metals (Jang et al., 2017). Moreover, their underdeveloped detoxification, excretion, immune, and enzymatic metabolic functions make them particularly vulnerable to environmental hazards. Consequently, ensuring the environmental safety of children’s activity spaces is of critical importance (National Institute of Environmental Research, 2016).

Currently, playground soils in children’s activity spaces in South Korea are classified under Category 1 of the Soil Contamination Concern Criteria according to the Soil Environment Conservation Act (Ministry of Environment, 2021). This category applies the same contamination criteria as agricultural lands, orchards, pastures, and cemeteries, assessing contamination based on total heavy metal content and parasite (egg) testing.

This study aims to evaluate the environmental safety of playground sand, taking into account the behaviors of children during play and the practical conditions under which they interact with the sand. To do this, we tested the soil from playgrounds in densely populated areas of Gyeonggi Province for parasitic eggs and fecal coliforms, assessing potential microbiological contamination from play activities. We also performed heavy metal analysis as required by legal standards and conducted in vitro bioaccessibility tests to measure children’s actual exposure to heavy metals through hand-to-mouth and direct contact behaviors with the soil. This combined approach provides a comprehensive assessment of potential environmental hazards related to children’s direct interactions with playground sand.

2.1. Study subjects

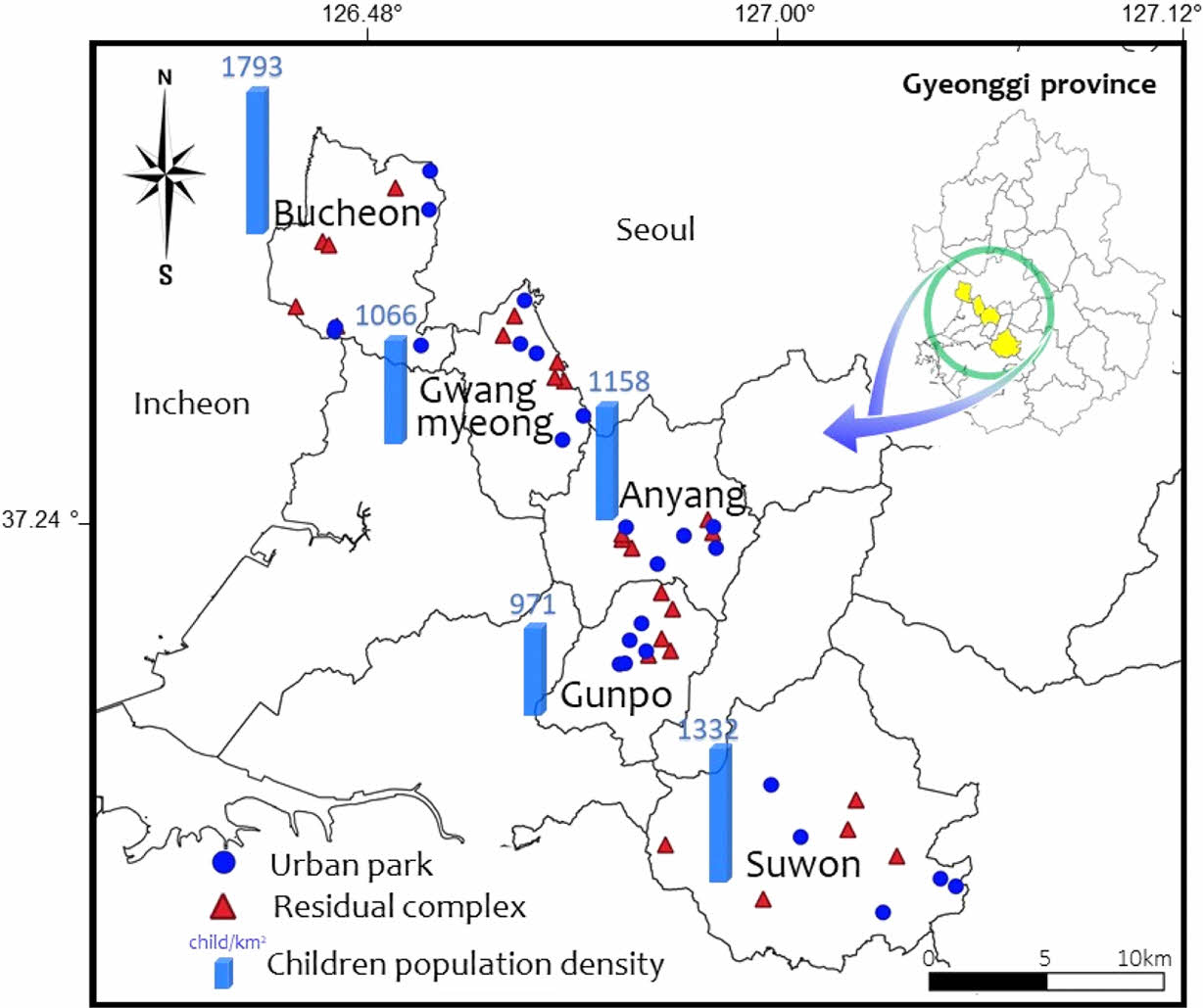

This study selected five cities in Gyeonggi Province with the highest child population density (Bucheon, Suwon, Anyang, Gwangmyeong, and Gunpo) based on the 2019 population data from the Korean Statistical Information Service (KOSIS, National Statistical Portal, 2023). The study targeted playgrounds using soil as flooring material, registered in the Child Play Facility Safety Management System of the Ministry of the Interior and Safety (Ministry of the Interior and Safety, 2023). Among the selected sites, 12 playgrounds were installed in children’s parks, and 13 playgrounds were located in neighborhood parks, totaling 25 playgrounds in urban parks. Additionally, 25 playgrounds within residential complexes were selected, making a total of 50 sand-based playgrounds included in this study. Fig. 1

2.2. Sample collection method

Soil samples were collected once during the spring season (April 5, 2023 – June 12, 2023), when children’s activities and pet walking were at their peak. Following the Soil Contamination Standard Test Method (National Institute of Environmental Research, 2022b), five sampling points were designated for each selected playground: one central point and four additional points located 5~10 m away in the east, west, south, and north directions. Surface soil samples (0~15 cm) from these five points were evenly collected and homogenized. Approximately 1 kg of mixed soil per playground was used as an analytical sample.

2.3. Analytical methods

2.3.1. Moisture, organic matter, and pH testing

In this study, soil and surrounding environmental charac-teristics were investigated to assess the microbiological conta- mination in children’s activity space soils. The survival and growth of microorganisms in the soil can be influenced by various environmental factors such as temperature, humidity, organic matter content, and pH. In particular, the moisture content of the soil may be related to the survival of microorganisms. Therefore, the temperature, humidity, soil temperature, soil moisture content, organic matter content, and pH of the study sites were investigated to evaluate the impact of these factors on the concentration of fecal coliform bacteria.

According to the Soil Contamination Standard Test Method (National Institute of Environmental Research, 2022b), moisture content was quantified at 110°C, and organic matter content (% w/w) was determined by calculating the weight loss after combustion at 450°C for 45 minutes (Lee et al., 2016). Hydrogen ion concentration (pH) was analyzed using the glass electrode method (Orion Star A211, Thermo Scientific, USA) after sieving the dried sample through a 10-mesh (2 mm) sieve, following the Soil Contamination Standard Test Method (National Institute of Environmental Research, 2022b).

2.3.2. Biological testing

The legally required parasite (egg) test was conducted according to the Environmental Hazardous Factor Standard Test Method (National Institute of Environmental Research, 2022a). Parasite eggs were suspended in a saturated zinc sulfate solution and examined under an optical microscope (Optical Microscope Pascalbio EVOS XL, USA) to determine their presence.

Fecal coliform bacteria tests were conducted using two methods (membrane filtration and enzyme substrate method) simultaneously to more accurately and reliably assess the contamination status in children’s activity spaces. The membrane filtration method has the advantage of efficiently isolating and culturing microorganisms from solid samples, while the enzyme substrate method is a rapid technique for quantifying coliform bacteria. By comparing the differences in analysis methods based on sample characteristics, the aim was to evaluate the potential applicability of these methods when setting fecal coliform bacteria standards for playground soils in the future.

For fecal coliform analysis, 10 g of soil was mixed with 100 mL of peptone dilution solution, shaken at 200 rpm for 5 minutes, and the supernatant was separated. The sample was then quantified using the membrane filtration method and the enzyme-based quantification method (Colilert-18, IDEXX, USA), following the Water Pollution Standard Test Method (National Institute of Environmental Research, 2022c).

In the membrane filtration method, up to five randomly selected blue colonies indicative of fecal coliforms were inoculated onto TSA medium (BD Difco, USA) and subsequently subcultured on the same medium for pure isolation. The isolated strains were finally identified using the API 20E kit (bioMérieux, France), and bacterial species with an identification probability (ID%) of 90% or higher were selected.

2.3.3. Heavy metal content testing

To minimize changes in soil structure and organic matter during the drying process, the samples were dried at temperatures below 40°C, and to simulate children’s interaction with the soil as closely as possible, the samples were preserved in their original state and sieved through a 100-mesh (150 μm) sieve for analysis. The soil samples were pretreated and analyzed following the Soil Contamination Standard Test Method (National Institute of Environmental Research, 2022b).

The samples were pretreated using the total digestion method with hydrochloric acid and nitric acid, and Cd, Cu, As, Pb, Zn, Ni, and Cr were analyzed using Inductively Coupled Plasma-Optical Emission Spectrometry (ICP-OES; AU/5100, Agilent, USA). Hg was analyzed using Cold Vapor Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometry (CVAAS; FIMS 400, PerkinElmer, USA). Cr6+ was pretreated using the digestion solution method (sodium hydroxide and sodium carbonate-tartrate solution) and analyzed using Ultraviolet/Visible Spectrophotometry (UV-Vis; Lambda 465, PerkinElmer, USA). All analysis and quality assurance/quality control (QA/QC) procedures were conducted in accordance with the Soil Contamination Standard Test Method (National Institute of Environmental Research, 2022b).

2.3.4. Heavy metal pollution index assessment

(1) Single item index assessment

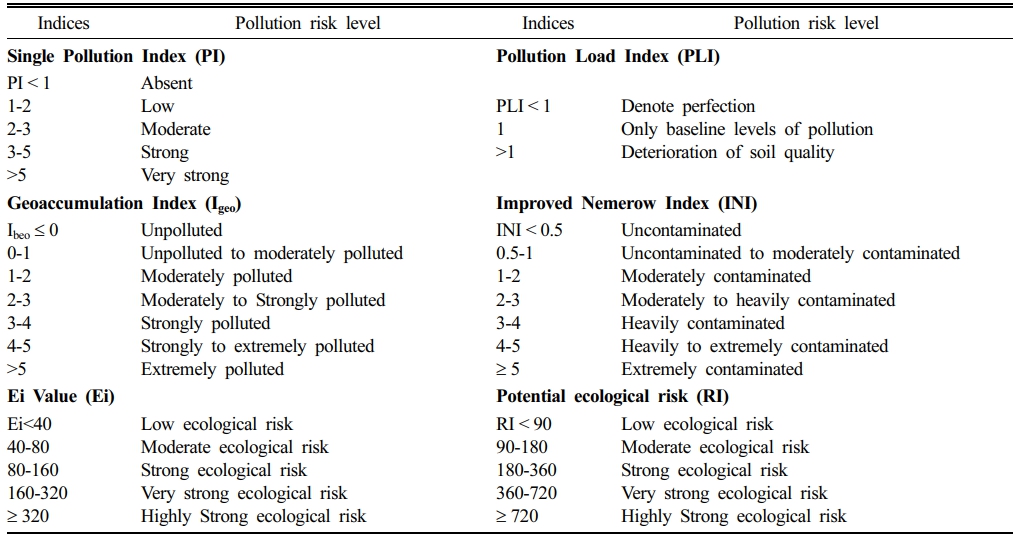

The Single Pollution Index (PI) and Geoaccumulation Index (Igeo) were used to assess the contamination levels of individual heavy metals in the soil (Kowalska et al., 2018; Muller, 1969).

To reflect the characteristics of the Gyeonggi Province region in the contamination assessment, only the average concentration values from the background sites selected in the 2020-2021 Soil Monitoring Network results (Soil and Groundwater Information System, 2020-2021) were extracted and applied. For Cr, which was not included in the Soil Monitoring Network, the study results of Yoon et al. (2009) on the natural background concentrations of Korean soil were applied (Table 3).

Ci : Heavy metal concentration of sample

Bi: Heavy metal concentration of background

1.5 : A constant generally used to regulate anthropogenic impacts (Kowalska et al., 2018; Muller, 1969)

(2) Composite pollution index assessment

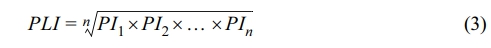

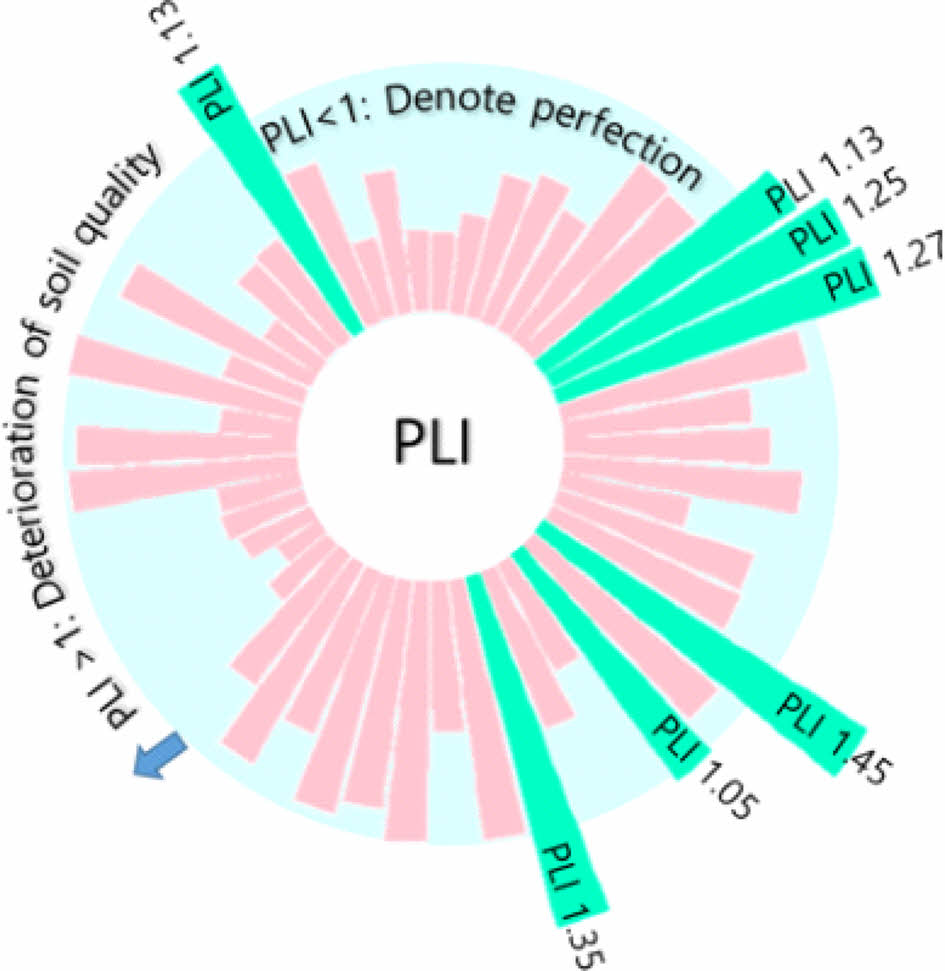

The Pollution Load Index (PLI), which indicates the degree of soil degradation due to heavy metal accumulation, is calculated as the geometric mean of PI. A PLI value exceeding 1 is considered to indicate that soil contamination exceeds the defined pollution criteria (Kowalska et al., 2018) (Table 1).

n : number of heavy metals analyzed

PI: calculated values for the Single Pollution Index

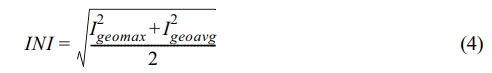

(3) Ecological risk assessment

The Potential Ecological Risk Index (RI) is an indicator used to assess the ecological risk posed by heavy metal contamination in soil. It reflects the combined effects of multiple heavy metal elements present in the environment on ecosystems, making it a crucial tool for evaluating ecological risks. The RI value classifies ecological risk into five levels, ranging from low to highly strong, to assess the potential ecological hazard posed by heavy metal contamination (Table 1).

Igeomax : the maximum value of Igeo

Igeoavg : the mean value of Igeo

The Potential Ecological Risk (RI) was used to evaluate the degree of ecological risk caused by heavy metal concentrations in water, air, and soil; it classifies ecological risk levels into five stages, from low to high (Table 1).

Ei : potential ecological hazard coefficient of heavy metals

Ti : The toxicity response coefficient of an individual metal (Zn = 1 < Cr = 2 < Pb = Cu = Ni = 5 < As = 10 < Cd = 30 < Hg = 40) (Hakanson, 1980)

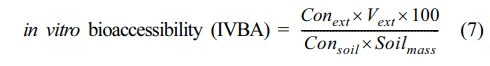

2.3.5. Bioaccessibility and solubility of heavy metals

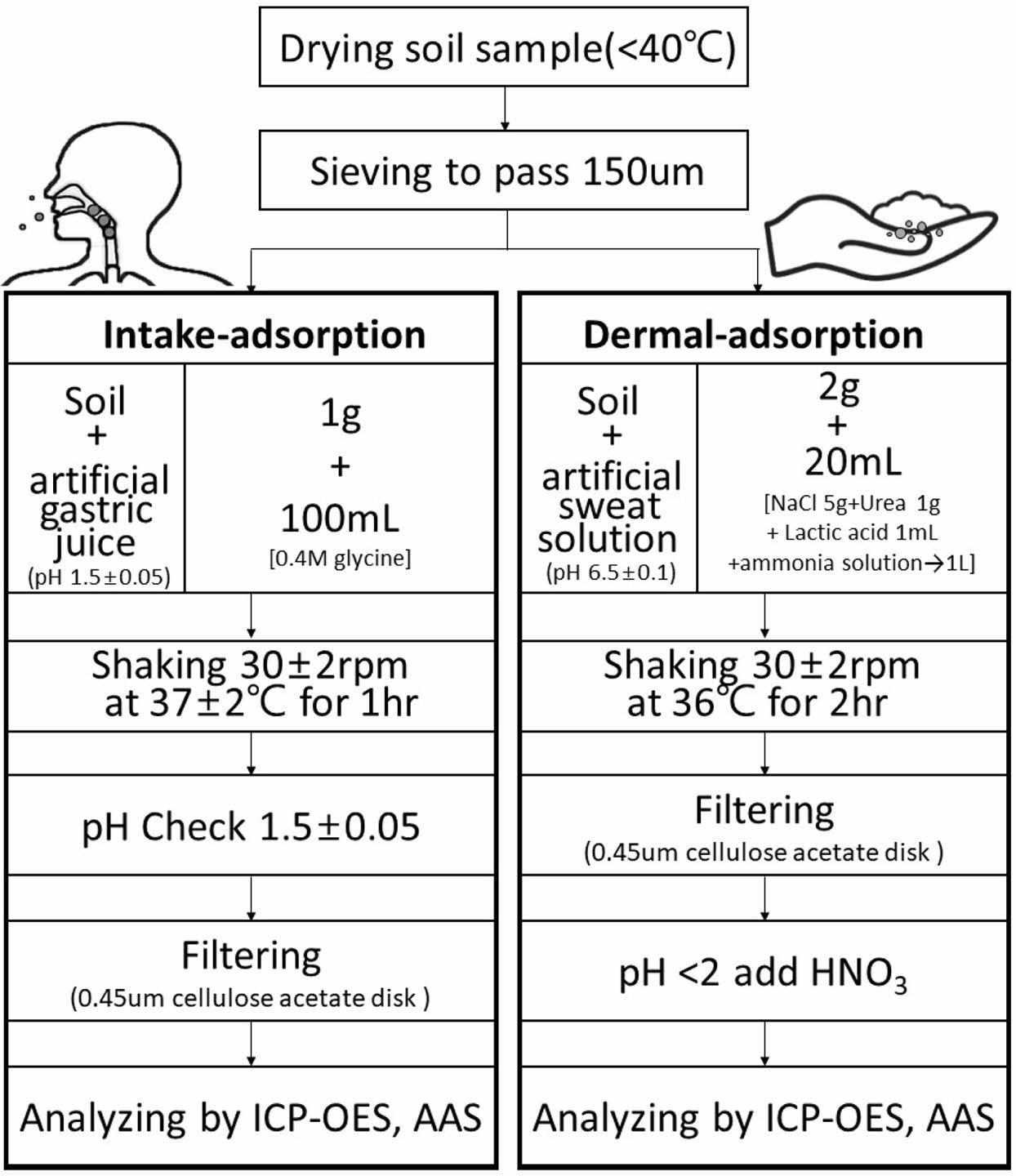

To assess the risk of heavy metal exposure, an in vitro test was conducted to evaluate oral and dermal bioaccessibility. The oral bioaccessibility of ingested soil was tested according to EPA Method 1340 (2017, USA), and the dermal bioaccessibility was assessed following the EU Standard EN1811 (2015) (Fig. 2).

To quantify the impact of heavy metals in playground soil on children, the bioaccessibility of soil particle ingestion and skin contact was calculated (USEPA, 2017).

Conext : concentration of extract (mg/L)

Vext : volume of extract (L)

Consoil : concentration of heavy metals in the soil (mg/kg)

Soilmass : mass of soil (kg)

2.3.6. Statistical analysis

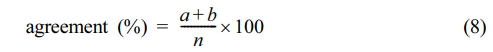

According to the study by Van Elsas et al. (2011), the survival of coliform bacteria is influenced by surrounding environmental factors. Based on this, Spearman rank correlation analysis was conducted using R software version 4.3.1 in this study. Spearman rank correlation analysis was used to examine the relationship between non-biological parameters (e.g., soil moisture content, organic matter content, etc.) and fecal coliform bacteria concentrations. Additionally, the correlation between heavy metal concentrations was assessed to evaluate the relationships among the concen- trations of each heavy metal. Cohen's kappa values were calculated using the kappa2 function of the irr package in R, and the agreement between different fecal coliform test methods was assessed using Single-Score Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC). To determine the compatibility between fecal coliform test methods, the agreement percentage (%) between different methods was reviewed (Oh et al., 2022).

a = all positives, b = all negatives, n= total number of samples

|

Fig. 1 Sampling site locations in Gyeonggi Province, South Korea. |

|

Fig. 2 Procedure for an in vitro bioaccessibility assay. |

|

Table 1 Categories of pollution and risk based on PI, Igeo, PLI, INI, Ei, and RI indices (Kowalska et al., 2018; Muller, 1969) |

|

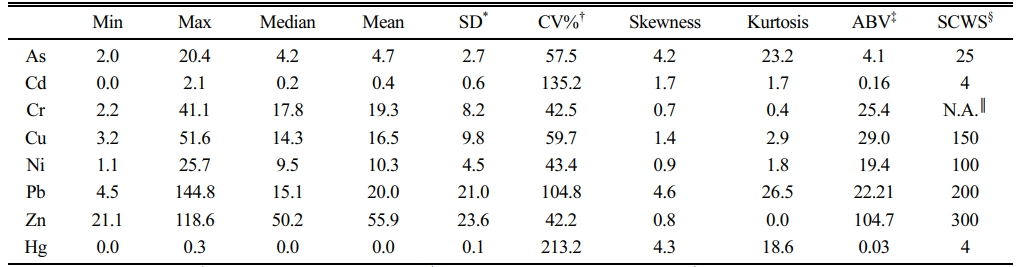

Table 3 Statistical summary of soil heavy metal concentrations (mg/kg) for children’s playground (n=50) |

*SD: Standard Deviation; †CV: Coefficient of Variation; ‡ABV: Average Background Value; §SCWS: Soil Contamination Warning Standards (Region 1); ║N.A.: Not Available |

3.1. Characteristics of the surrounding environment and soil of children’s activity spaces

At the time of sample collection, the average soil temperature in playgrounds within children’s activity spaces was 18.9°C (12.5-31.1°C), the average ambient temperature was 24.0°C (14.9-36.5°C), and the average ambient humidity was 36.2% (17.0-84.8%).

Animal feces were visually observed on the soil surface at one site (2%), and cigarette butts and various types of litter were found mixed in the soil at six playgrounds (12%).

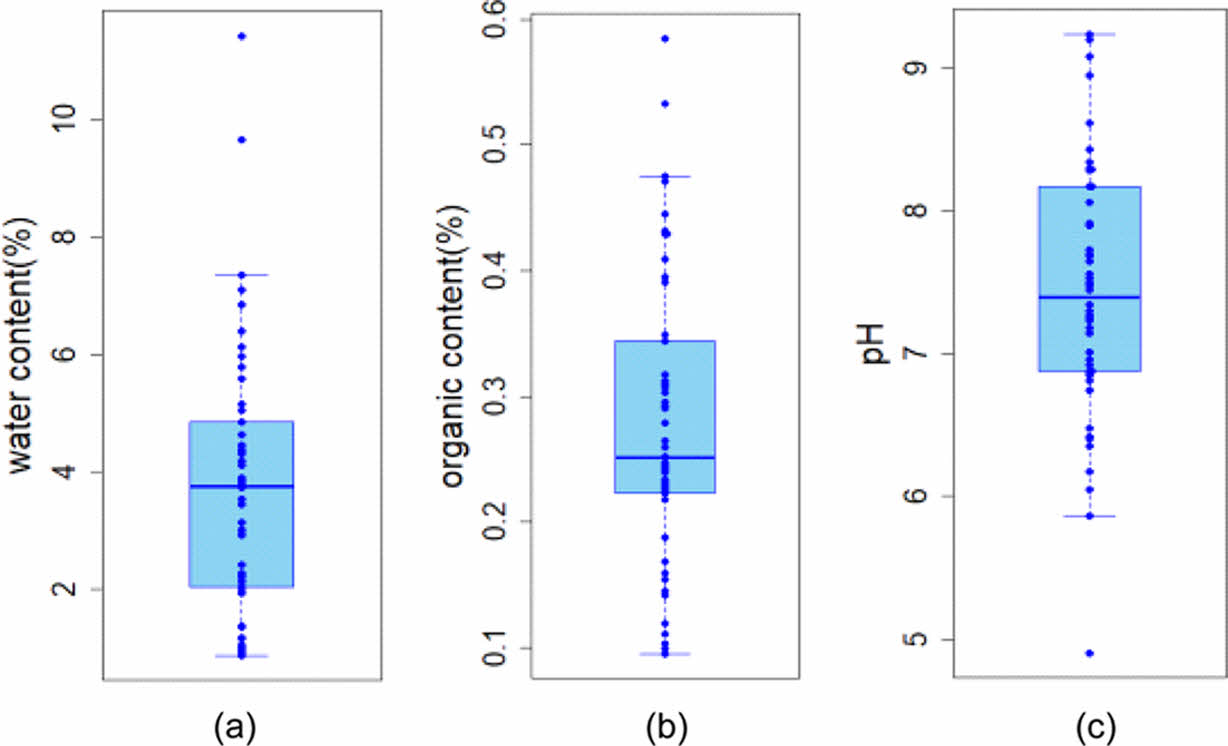

The average soil moisture content in playgrounds within the study area was 3.8% (0.9-11.4%), the average organic matter content was 0.3% (0.1-0.6%), and the average pH was 7.4 (4.0-9.2) (Fig. 3).

3.2. Biological examination results

3.2.1. Presence of parasites (eggs)

No parasitic eggs were detected in the soil of children’s playgrounds in this study, thereby meeting the environmental safety management standards of the Environmental Health Act.

3.2.2. Presence of fecal coliform bacteria

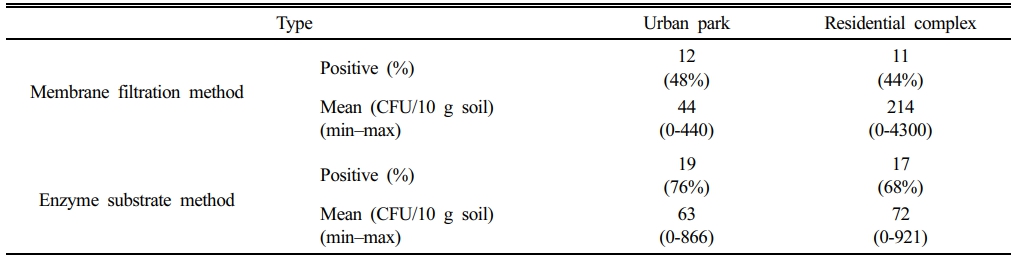

The average detected concentration of fecal coliforms in playground soil was 129 CFU/10 g soil using the membrane filtration method (MFM) and 68 CFU/10 g soil using the enzyme substrate method (ESM). Additionally, fecal coliforms were detected at 23 sites (46%) using the membrane filtration method and at 36 sites (72%) using the enzyme substrate method, indicating that the positive detection rate of the enzyme substrate method was higher than that of the membrane filtration method (Table 2).

3.2.3. Correlation between fecal coliform bacteria and abiotic variables

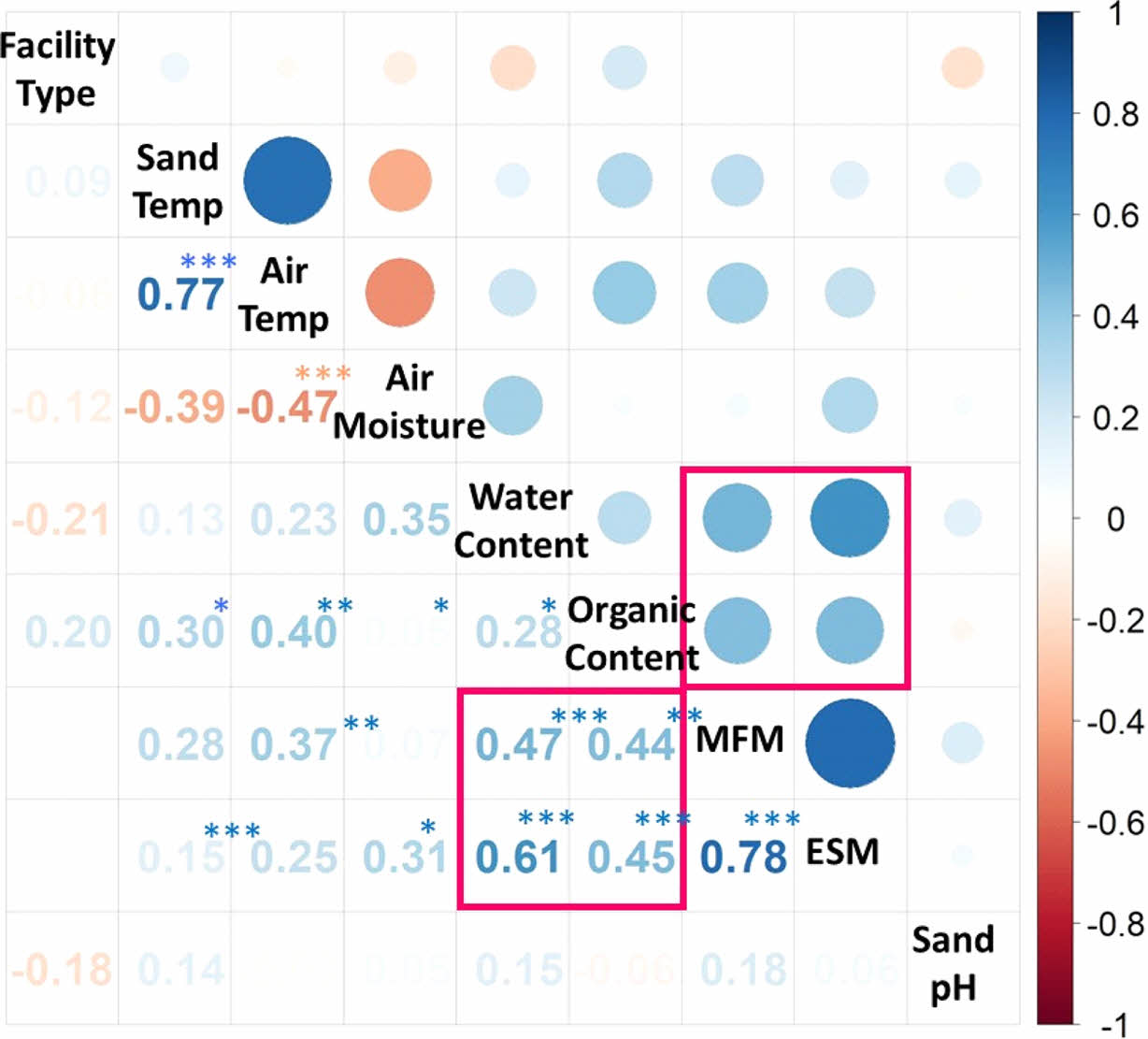

In this study, the relationship between fecal coliform proliferation in playground environments and abiotic factors (such as facility type, soil temperature, ambient temperature, ambient humidity, soil moisture content, and soil organic matter content) was examined using Spearman’s rank correlation analysis.

The results showed a significant correlation between fecal coliform concentration and soil moisture content (r = 0.47 (MFM)/0.61 (ESM)) as well as organic matter content (r = 0.44 (MFM)/0.45 (ESM)) (p < 0.01), indicating a weak to moderate positive correlation. These values were slightly lower than those reported in Badura et al. (2014), where the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient between Escherichia coli concentration (measured using the membrane filtration method) and moisture content was r = 0.51 (p < 0.001) in public playground soil.

On the other hand, no statistically significant correlations were observed with facility type (urban park/residential complex), ambient temperature, ambient humidity, soil temperature, or soil pH (Fig. 4). This suggests that, given the outdoor exposure characteristics of playground soil, internal soil properties (such as moisture and organic matter content) may have a greater impact on fecal coliform survival than temporary meteorological changes.

3.2.4. Comparison of fecal coliform detection consistency between analytical methods

Based on the study by Oh et al. (2022), which reported variability in results depending on the analysis method used for microbial detection, this study compared the qualitative (detection/non-detection) and quantitative (concentration) agreement between two methods to assess the applicability of coliform bacteria testing in children’s activity space soils.

The qualitative agreement (detection/non-detection) between the two methods was 74%, which was slightly lower than the 80% agreement reported in Oh et al. (2022) for total coliforms analyzed in groundwater and drinking water.

Additionally, Cohen's Kappa analysis showed a Kappa value of 0.498 and a Z-value of 4.07, indicating a moderate agreement between the two test methods, with a statistically significant difference (p = 4.7e-5). According to Landis and Koch's classification, this result is interpreted as a moderate level of agreement.

Furthermore, to evaluate the agreement in detected concen- trations, a Single Score Intraclass Correlation (ICC) analysis was performed, yielding an ICC value of 0.47, indicating a moderate to high level of agreement. The F-test results confirmed that the correlation between the two test methods was greater than zero (F(49,50) = 2.78, p = 2.25e-04), which was statistically significant.

3.2.5. Identification of fecal coliform bacteria

Bacterial identification of 23 fecal coliform-positive colonies isolated using the membrane filtration method revealed that the most frequently identified bacterium was Escherichia coli, which was isolated from 11 sites. At one site, both E. coli and Kluyvera spp. were isolated, while Stenotrop- homonas maltophilia was identified in one sample. The remaining 10 isolates were unidentified.

Among the commonly occurring E. coli strains in both humans and animals, some pathogenic strains can cause sepsis in newborns and are among the most common global causes of gastroenteritis and diarrhea (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, 2013).

Stenotrophomonas maltophilia is a bacterium found in natural environments such as water, soil, and plants. While it is not highly virulent, it can act as an opportunistic pathogen, causing urinary tract infections in immunocompromised patients or those with underlying conditions (Looney et al., 2009).

3.3. Heavy metal content and characteristics in the soil of children’s activity spaces

The analysis of heavy metal concentrations in children’s activity space playground soils showed that all sites were within the Soil Contamination Concern Standard (Region 1) limits (Table 3). The average concentrations of heavy metals relative to the Soil Contamination Concern Standard were as follows: As 18.8%, Zn 18.4%, Cu 10.8%, Cd 10.6%, Ni 10.3%, Pb 9.9%, and Hg 0.6%.

The descriptive statistical analysis of heavy metal concen- trations (Table 3) revealed that Hg, Cd, Pb, Cu, and As exhibited relatively high spatial variability (Coefficient of Variation, CV). Specifically, Hg (213.2%), Cd (135.2%), Pb (104.8%), and Cr (98.5%) showed particularly high variability. The variability of heavy metal concentrations in playground soils tended to be higher than that of the background levels in Gyeonggi Province. Notably, Pb and Hg showed variability coefficients 2.3 times and 1.5 times higher, respectively, compared to the background areas of Gyeonggi Province. This suggests that heavy metal concentrations in playground soils exhibit greater fluctuations than those in other areas of Gyeonggi Province.

Pb exhibited the highest kurtosis (26.5), which may be attributed to sources such as paints used in playground equipment, Pb-containing coatings on nearby buildings, previously accumulated Pb in the soil, and traffic-related activities (Huang et al., 2021).

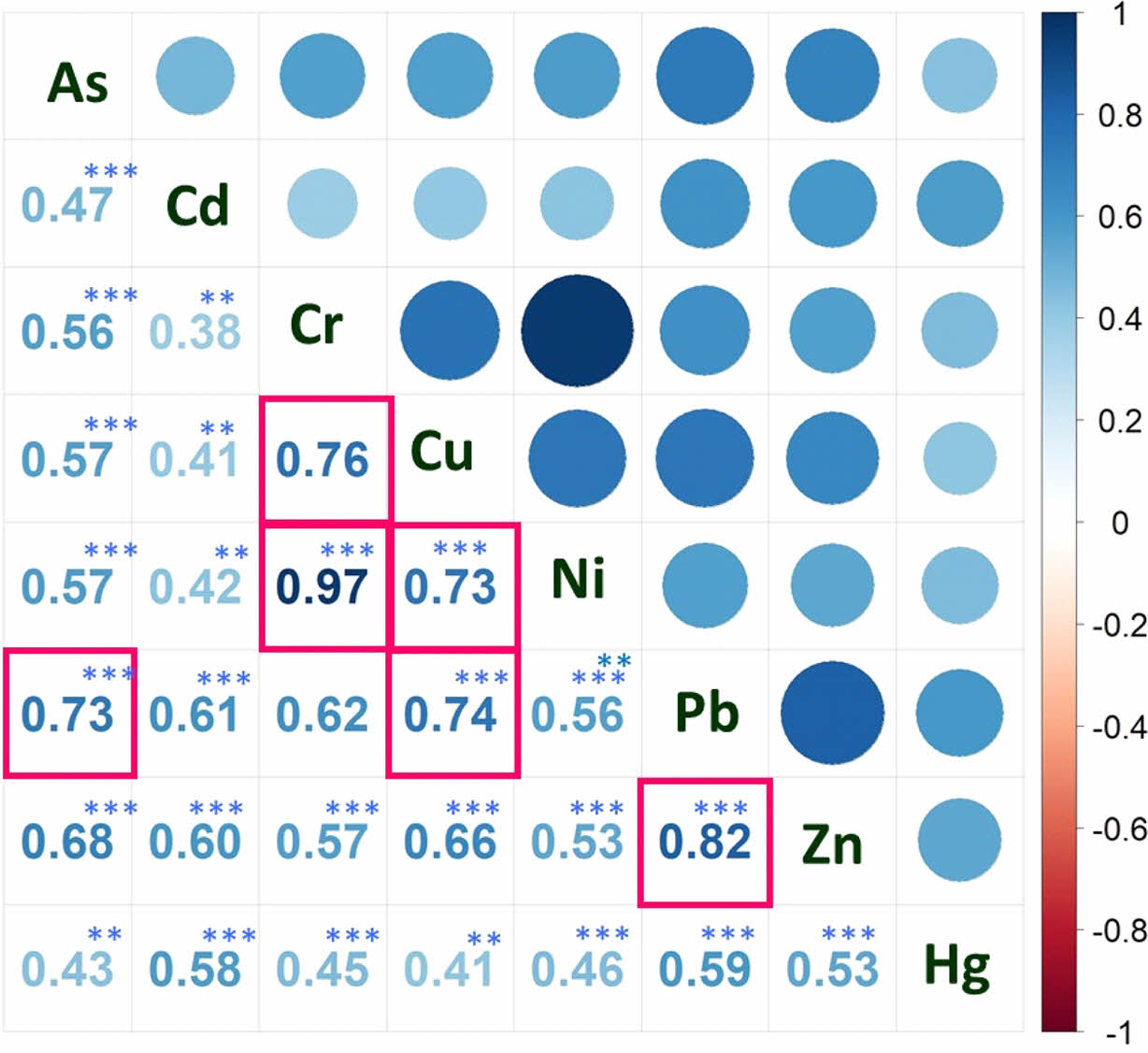

The Spearman rank correlation analysis of individual heavy metal concentrations showed the strongest correlation between Ni and Cr (r = 0.97, p = 2.2e-16), followed by significant correlations between Pb and Zn (r = 0.82, p = 2.3e-13), Pb and As (r = 0.73, p = 2.3e-09), and Pb and Cu (r = 0.74, p = 1.2e-09). Additionally, Cu showed a strong correlation with Ni (r = 0.73, p = 1.55e-09), suggesting a potential common source for these heavy metals (Fig. 5).

When strong correlations are observed between specific heavy metals, it is likely that both geological origins and industrial emissions contribute simultaneously to their presence in the study area (Huang et al., 2021).

3.4. Heavy metal pollution index of soil in children’s activity spaces

3.4.1. Characteristics of individual pollution index (PI)

The individual heavy metal contamination levels of play- ground soils were assessed using the Single Pollution Index (PI). The average PI values were as follows: Cd (2.7) > As (1.2) > Pb (0.90) > Hg (0.81) > Cr (0.76) > Cu (0.56) > Ni = Zn (0.53). Cd and As exhibited higher values than the heavy metal concentrations in the surrounding background areas of Gyeonggi Province.

Cd, the most highly contaminated metal, was categorized as non-polluted (42%), low pollution (32%), moderate pollution (4%), high pollution (2%), and very high pollution (20%). For As, 46% of samples were in the non-polluted category, 50% in the low pollution category, and 2% each in the moderate and high pollution categories. Additionally, 2% of Pb and 4% of Hg samples were classified as being in the very high pollution category.

Ni and Zn showed the lowest contamination levels, with 96% of the samples classified as non-polluted and 4% classified as low pollution.

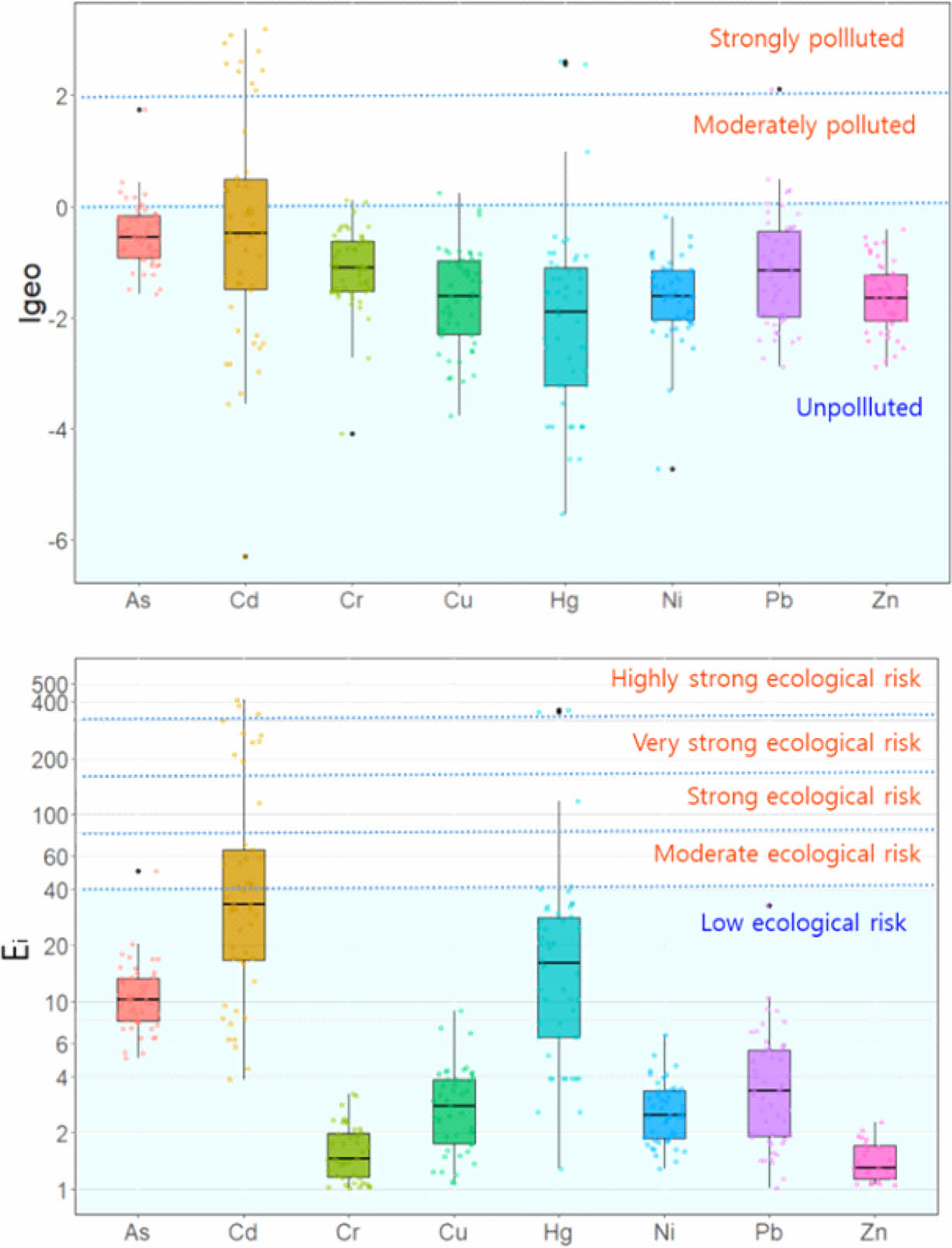

The pollution status based on PI showed that 77% of the samples were non-polluted, 18.5% were in low pollution, 1% in moderate pollution, 0.5% in high pollution, and 3% in very high pollution. In contrast, the pollution assessment using Igeo, which accounts for variability in natural background levels, showed 91% of samples as non-polluted, 5% as non-polluted to moderately polluted, 0.5% as moderately polluted, 3% as moderately to highly polluted, and 0.5% as highly polluted, indicating a lower pollution level compared to the PI results.

The average Igeo values were ranked as follows: Cd (-0.4) > As (-0.52) > Cr (-1.13) > Pb (-1.15) > Zn (-1.63) > Ni (-1.65) > Cu (-1.67) > Hg (-2.06).

By category, Ni and Zn were classified as non-polluted for all samples, while Cu (98%), Cr (96%), Hg (94%), Pb (88%), As (84%), and Cd (66%) were also classified as non-polluted. However, 20% of Cd samples exhibited moderate to high pollution levels (Fig. 6).

The potential ecological hazard coefficient (Ei), which evaluates the potential ecological risk of individual heavy metals, showed that Cd posed a high ecological risk, while Hg posed a moderate ecological risk. All other elements were classified as low ecological risk, with values ranked as follows: Cd (81.1) > Hg (32.3) > As (11.5) > Pb (4.5) > Cu (2.8) > Ni (2.7) > Cr (1.5) > Zn (1.1) (Fig. 6).

3.4.2. Characteristics of the combined pollution index (PLI)

To demonstrate the extent of soil quality deterioration due to heavy metal accumulation (Kowalska et al., 2018), the Pollution Load Index (PLI) was calculated as the geometric mean of PI. The average PLI was 0.69 (0.19-1.45), with 7 sites (14%) classified as having degraded soil quality (PLI > 1) (Fig. 7).

3.4.3. Biological index characteristics

The Improved Nemerow Index (INI) is a comprehensive index used to evaluate soil heavy metal contamination by combining the maximum exceedance rate and the average exceedance rate of each heavy metal, providing a quantitative assessment of soil pollution (Hakanson, 1980). In this study, the INI results showed that 8% of the samples were classified as non-polluted, 28% as non-polluted to moderately polluted, 52% as moderately polluted, and 12% reached a moderately to highly polluted level. The average Risk Index (RI) value was 137, indicating a medium risk level. In particular, Hg, Cd, and Pb pose higher ecological risks compared to other heavy metals due to their high toxicity response coefficients and high concentration levels. Specifically, 20% of Cd, 4% of Hg, and 0.5% of Pb samples were classified as medium or higher risk. Among these, 8% of Cd and 4% of Hg samples were found to be at a considerable risk level.

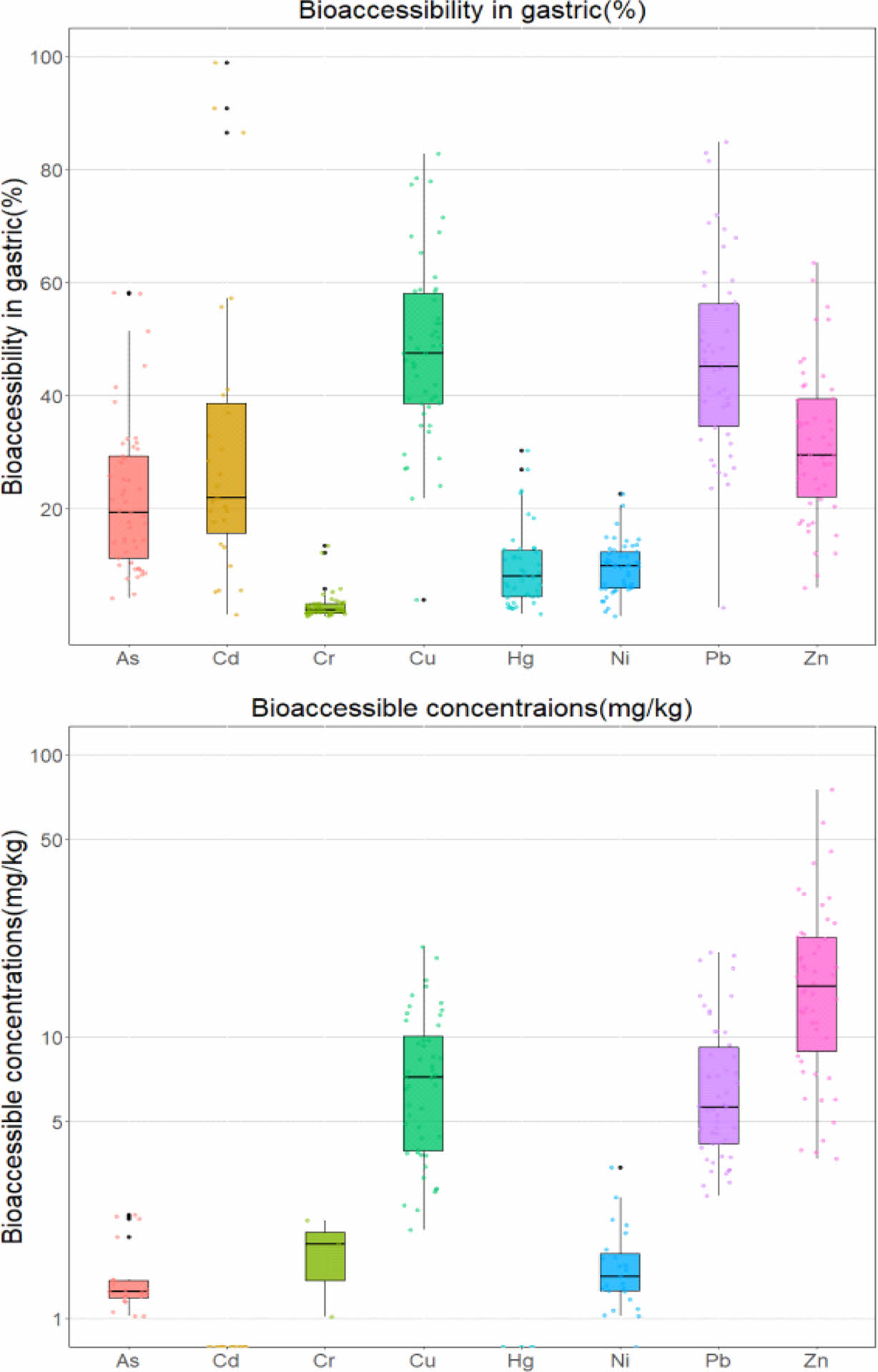

3.5. Bioavailability of heavy metals in playground soil

The average oral in vitro bioaccessibility of playground soil in children’s activity spaces was 23%, with Cu (47.8%) exhibiting the highest bioaccessibility. The bioaccessibility of Pb was the second highest at 46.3%, followed by Zn (31.4%) > As (21.5%) > Cd (16.9%) > Ni (9.4%) > Hg (8.1%) > Cr (2.6%) (Fig. 8).

When comparing the bioavailability values obtained in this study with the internationally recognized exposure bioavailability values used in risk assessment, the oral bioavailability of arsenic (As) was assumed to be 60% by the U.S. EPA; however, the value observed in this study was 21.5%, which is relatively lower. In contrast, for lead (Pb), the U.S. EPA assumed an oral bioavailability of 30%, whereas the value observed in this study was 46.3%, which was higher. These differences may be attributed to variations in the physicochemical properties of playground soil and the forms in which heavy metals are present (U.S. EPA, 2012a,b).

The estimated oral heavy metal bioavailable transfer amounts, considering bioaccessibility, were ranked as follows: Zn (18.2 mg/kg) > Cu (7.51 mg/kg) > Pb (7.4 mg/kg) > Ni (0.99 mg/kg) > As (0.71 mg/kg) > Cd (0.03 mg/kg) (Fig. 8).

The average dermal in vitro bioaccessibility was 0.3%, significantly lower than oral absorption rates, with the following ranking: Cd (0.68%) > As (0.56%) > Cu (0.49%) > Ni (0.29%) > Zn (0.24%) > Hg (0.01%) > Cr ≈ Pb (0.00%).

According to Solt et al. (2015), children exposed to Pb-contaminated soil in residential areas showed a tendency for increased blood pressure levels. Similarly, Carrizales et al. (2006) estimated that approximately 87% of the total lead in children’s blood resulted from exposure to soil and dust, suggesting that high soil Pb content may significantly increase Pb bioavailable transfer to children through unintentional ingestion.

|

Fig. 3 Physico-chemical characteristics of children’s playground soil (n=50), (a) water content, (b) organic content, (c) pH. |

|

Fig. 4 Spearman correlation of fecal coliform in children’s playground soil. Facility type: Urban park, Residual complex. MFM: Membrane Filtration Method, ESM: Enzyme Substrate Method; *p<.05, **p<.01, ***p<.001. |

|

Fig. 5 Spearman correlation of heavy metals in the soil of children’s playgrounds. Coefficients above 0.7 are highlighted in red boxes. **p<.01, ***p<.001. |

|

Fig. 6 Igeo and Ei in the study areas. |

|

Fig. 7 PLI values in the study areas. |

|

Fig. 8 Bioaccessibility (%) and bioaccessible concentrations (mg/kg) in both gastric phase of potentially harmful elements in children’s playground soil. |

This study comprehensively evaluated the environmental safety of playground soil in children’s activity spaces located in five cities with high child population density in Gyeonggi Province. All 50 study sites met the environmental safety standards for heavy metals and parasitic eggs (ova) set by the Environmental Health Act. Fecal coliform bacteria were detected in 23 sites (46%) using the membrane filtration method and in 36 sites (72%) using the enzyme substrate method. The detection results of the membrane filtration method and the enzyme substrate method showed moderate consistency, but the positive detection rate was higher with the enzyme substrate method. This difference may be attributed to the characteristics of the soil samples and the sensitivity differences of the analytical methods, suggesting the need for further research to establish standardized analytical procedures for fecal coliform bacteria testing and ensure reliable detection methods.

Furthermore, fecal coliform bacteria concentration showed a significant correlation with soil moisture content and organic matter content. Future studies should analyze the seasonal variations and changes in fecal coliform bacteria concentrations following rainfall to improve the accuracy of microbiological environmental assessments.

The heavy metal concentrations in playground soil showed higher levels of Cd and As compared to the background areas of Gyeonggi Province, while Ni showed a strong correlation with Cd, and Pb showed a strong correlation with Zn, As, and Cu. The heavy metal contamination assessment revealed that Cd, As, and Hg had the highest contamination levels, and these were identified as major pollutants that could cause ecological risks. Due to heavy metal accumulation, approximately 14% of the sampling points showed soil quality degradation, and the Potential Ecological Risk Index (RI) was rated as a medium risk (137). In the heavy metal bioaccessibility assessment, the average oral bioaccessibility was 23%, with Cu and Pb showing bioaccessibility greater than 46%. This indicates a significant risk of children being exposed to heavy metals via the oral route from playground soil, and highlights the need for effective management of metals with high bioaccessibility, such as Pb.

The results of this study indicate that while the environmental safety of playground soil meets legal standards, there are still potential risks from heavy metals and biological contamination. Therefore, continuous monitoring and further research on heavy metal and fecal coliform contamination are essential. This will ensure the safety of playground surfaces and provide a healthy and safe environment where children can play.

This work was partially supported by the National Institute of Environmental Research's Local Government Health and Environmental Research under Grant (number NIER-2023-01-03-002).

- 1. Badura, A., Luxner, J., Feierl, G., Reinthaler, F. F., Zarfel, G., Galler, H., Pregartner, G., Riedl, R., and Grisold, A. J. 2014, Prevalence, Antibiotic Resistance Patterns and Molecular Characterization of Escherichia coli from Austrian Sandpits, Environ. Pollut., 194, pp. 24-30.

-

- 2. Carrizales, L., Razo, I., Téllez-Hernández, J. I., Torres-Nerio, R., Torres, A., Batres, L. E., Cubillas, A.-C., and Díaz-Barriga, F. 2006, Exposure to Arsenic and Lead of Children Living Near a Copper-Smelter in San Luis Potosi, Mexico: Importance of Soil Contamination for Exposure of Children, Environ. Res., 101(1), 1-10.

-

- 3. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, 2013, Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance in Europe 2012, Annual Report of the European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Network (EARS-Net), ECDC, Stockholm. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.2900/93403.

-

- 4. Hakanson, L., 1980, An Ecological Risk Index for Aquatic Pollution Control: A Sedimentological Approach, Water Res., 14(8), 975-1001.

-

- 5. Huang, J., Wu, Y., Sun, J., Li, X., Geng, X., Zhao, M., Sun, T., and Fan, Z., 2021, Health Risk Assessment of Heavy Metal(loid)s in Park Soils of the Largest Megacity in China by Using Monte Carlo Simulation Coupled with Positive Matrix Factorization Model, J. Hazard. Mater., 415, 125629.

-

- 6. Jang, J.-W., Kim, Y.-H., Lee, Y.-K., Cho, M.-C., Jeong, H.-Y., Cho, Y.-K., Kim, E.-S., and Kim, D.-J., 2017, Influence of Playground Facilities and Environmental Factors on Heavy Metal Concentrations in Sand at Children¡¯s Playgrounds in Gwangju, J. Korea Soc. Waste Manag., 34(4), 369-377.

-

- 7. Jang, J.-Y., Kim, S. -Y., Kim, S.-J., Lee, K. -E., Cheong, H.-K., Kim, E.-H., Choi, K. -H., and Kim, Y.-H., 2014, General Factors of the Korean Exposure Factors Handbook, J. Prev. Med. Public Health, 47(1), 7-17.

-

- 8. Jin, Y., O¡¯Connor, D., Ok, Y. S., Tsang, D. C. W., Liu, A., and Hou, D., 2019, Assessment of Sources of Heavy Metals in Soil and Dust at Children¡¯s Playgrounds in Beijing Using GIS and Multivariate Statistical Analysis, Environ. Int., 124, 320-328.

-

- 9. Kowalska, J. B., Mazurek, R., Gąsiorek, M., and Zaleski, T., 2018, Pollution Indices as Useful Tools for the Comprehensive Evaluation of the Degree of Soil Contamination - A Review, Environ. Geochem. Health, 40, 2395-2420.

-

- 10. Lee, S.-J., Kim, J.-J., and Jung, S.-W., 2016, Study on Soil Organic Matter Content at Expanded Soil Monitoring Network Sites, J. Korean Soc. Environ. Eng., 38(12), 641-646.

-

- 11. Looney, W. J., Narita, M., and Mühlemann, K., 2009, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia: An Emerging Opportunist Human Pathogen, Lancet Infect. Dis., 9(5), 312-323.

-

- 12. Ministry of Environment, 2021, Environmental Health Act.

- 13. Ministry of the Interior and Safety, 2023, Children¡¯s Playground Safety Management System, Available at: https://www.cpf.go. kr/cpf/ (Accessed: 1 April 2023).

- 14. Muller, G., 1969, Index of Geoaccumulation in Sediments of the Rhine River, J. Geol., 2, 108-118.

- 15. National Institute of Environmental Research, 2007, Study on Exposure and Risk Assessment of Hazardous Substances in Children¡¯s Products.

- 16. National Institute of Environmental Research, 2016, Korean Exposure Factors Handbook for Children.

- 17. National Institute of Environmental Research, 2022a, Environmental Hazardous Substance Test Standards.

- 18. National Institute of Environmental Research, 2022b, Soil Contamination Standard Test Method.

- 19. National Institute of Environmental Research, 2022c, Water Pollution Standard Test Method.

- 20. Oh, S.-E., Chung, J.-Y., Sim, K.-S., Kim, Y.-J., Lee, H.-I., Moon, H.-C., Choi, I.-W., and Oh, J.-G., 2022, Comparison of Qualitative Test Methods for Total Coliforms, Korean Soc. Toxicol. Health, Korean Toxicol. Soc. Symp. Sci. Present., 5, 271.

- 21. Soil and Groundwater Information System, 2023, Available at: https://sgis.nier.go.kr/web (Accessed: 10 January 2023).

- 22. Solt, M. J., Deocampo, D. M., and Norris, M., 2015, Spatial Distribution of Lead in Sacramento, California, USA, Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 12(3), 3174-3187.

-

- 23. Statistics Korea, 2023, KOSIS Population Information, Available at: https://kosis.kr/index/index.do (Accessed: 1 April 2023).

-

- 24. US Environmental Protection Agency, 2012a, Recommendations for Default Value for Relative Bioavailability of Arsenic in Soil, OSWER 9200.1-113.

- 25. US Environmental Protection Agency, 2012b, Estimation of Lead Bioavailability in Soil and Dust: Evaluation of the Default Value for the Integrated Exposure Uptake Biokinetic Model for Lead in U.S. Children, OSWER 9200.1-113. Available at: https://www.epa.gov (Accessed: 14 February 2024).

- 26. US Environmental Protection Agency, 2017, Method 1340 In Vitro Bioaccessibility Assay for Lead in Soil.

- 27. van Elsas, J. D., Semenov, A. V., Costa, R., and Trevors, J. T., 2011, Survival of Escherichia coli in the Environment: Fundamental and Public Health Aspects, ISME J., 5(2), 173-183.

-

- 28. Yoon, J., Kim, D., Kim, T., Park, J., Jung, I., Kim, J., and Kim, H., 2009, Evaluation of Natural Background Levels of Heavy Metals in Korean Soil, J. Soil Groundwater Environ., 14(3), 32-39.

This Article

This Article

-

2025; 30(1): 37-48

Published on Feb 28, 2025

- 10.7857/JSGE.2025.30.1.037

- Received on Jan 10, 2025

- Revised on Feb 3, 2025

- Accepted on Feb 26, 2025

Services

Services

- Abstract

1. introduction

2. materials and methods

3. results and discussion

4. conclusions

- Acknowledgements

- References

- Full Text PDF

Shared

Correspondence to

Correspondence to

- Lee Hyunkyung

-

Gyeonggi Province Institute of Health and Environment, Gyeonggi Province 16381, Korea

- E-mail: leeapple@gg.go.kr